Notes:

- A

pdf version of this paper is available.

1. Introduction: Individual differences

While the people who make up a film's audience certainly share some

characteristics (for example, a preference for a film genre, for a particular

director and/or performer, or for a particular theme), they undoubtedly show, as

in any other area of experience, individual differences. Viewers differ

more or less markedly in their previous knowledge of the film genre, their

personal experiences and their beliefs and attitudes - all elements that influence expectations, reactions and judgments about the film.

Individual differences, however, are also a fascinating field of exploration

with respect to the concept of personality. After all, what makes

people

unique individuals depends on a variety of factors, some of which are biological

and innate, while others are the result of the experiences we have gone through

since the day we were born, including our socialization processes in the context

of our culture. The "innate" and the "learned" are not two separate domains, but

are inextricably linked in forging our special way of being unique

(though this should not make us forget what makes individuals similar to each

other).

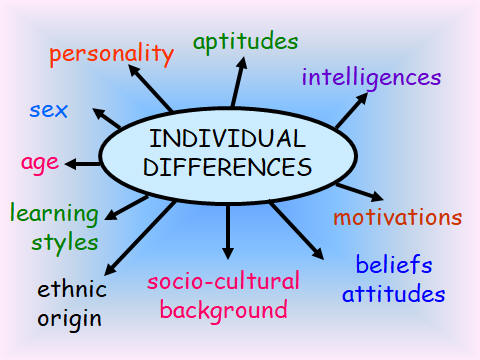

Individual differences can be described and have been studied with reference to

a variety of concepts (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1

People are different in terms of a

range of variables, from the basic biological facts of age and

sex to more subtle psychological constructs like aptitudes,

motivations, beliefs and attitudes to sociocultural aspects

like social/economic background and ethnic origin. As can be seen, this "map"

includes terms which could be considered of a more general nature:

personality, for instance, could justifiably be meant to include some or

most of the other variables. However, there are two classes of

variables which, while still very much identifiable as descriptors of

personality, deserve to be dealt with in more detail since they are not

so often taken into consideration: learning styles and

(multiple) intelligences. The present work concentrates on these

two basic constructs, while most of the other ones appearing in Fig. 1

are explored, in relation to cinema audiences and their movie

preferences, in another paper (Note 1). Styles and intelligences have

never been used in the exploration of movie preferences (neither in

terms of how styles and intelligences can predict individual movie

preferences nor in terms of what movie preferences can tells us about

viewers' styles and intelligences) and this paper is meant to provide

some preliminary observations as well as to point to some possible

pathways for future research.

2. "Learning", "thinking", "cognitive" styles

A word of warning about the nature of "styles" is in order, since

various terms are used in the literature, sometimes with partially

overlapping meanings. The term "learning style" is perhaps the most general

one, and it refers to the different ways in which people perceive and

process information. Although "learning" could be used to

describe any kind of information processing (i.e. most, if not all, of

our mental activity), learning styles have mostly been studied in

relation to pedagogical contexts, as descriptors of how learners (in the

stricter sense of "students") approach

tasks in a more or less formal educational situation. In this wider

sense, learning styles have sometimes been made to include, not

just cognitive/thinking styles, but other measures of individual

differences impacting on learning. Thus,

for example, people have been found to differ in their preferences for sensory

modalities (some may be more visual, some more auditory, still others may

prefer a kinesthetic approach, i.e. based on the use of the body and its

movements); and people also show different social attitudes (e.g. being more or less

introverts rather than extroverts).

In most other cases, though, styles have been explored in

relation to the individual ways of

processing information - i.e. as thinking styles, or, by

reference to the workings of the human mind, as cognitive

styles.

Boscolo (1981: 68) defines a thinking style as “A way of

processing information which the subject adopts predominantly, which is

consistent over time and extends to different tasks”.

This definition points to the prevailing (thus not exclusive)

way of information processing, to its stable nature (which

could even be taken as a personality trait) and to its use in a

variety of tasks and contexts.

Cognitive styles refer to the typical ways each individual

processes information in his or her mind - summarizing in the term

"process" a series of operations variously described as acquiring,

storing, retrieving, and reusing information. In this cognitive

perspective, which considers the person actively involved in processing

new information (information which in turn functions as a catalyst for

continuous restructuring of knowledge), cognitive styles emphasize the

different ways in which this restructuring can take place in the mind.

Most of the models proposed to describe cognitive styles are based

on bipolar oppositions in which two terms are assumed to be the extremes

of an ideal continuum on which individual people actually

position themselves: one of the classic models of cognitive styles had

been proposed in the 1940s, i.e. the opposition field dependent

vs field/independent(Note 2). While those who are field

dependent have more difficulty and/or take longer to separate a figure

from the context in which it appears, those who are field independent

can perceive elements as more or less separate from the surrounding

context more easily and quickly: this has led to the hypothesis that

there could be people "who see the forest but not the trees", and vice

versa, with obvious consequences for a more global rather than

analytical processing of information. Thus some people may tend towards an analytical style: they prefer to start

from the parts to get to the whole, like to consider details, reason logically,

willingly focus on the differences between things. Others, on the other hand,

may tend towards a global style: they start from an overall vision and

from the general context, organize the information more simultaneously, find it

easy to make a synthesis, focus more willingly on the similarities between

things.

Other distinctions, however, have been explored. For example, people also differ in their tendency towards reflectivity: more

reflective people

carefully consider facts and possible options, make more objective judgments,

require longer processing times. Others are more impulsive: they make

decisions based on sensations and essential information, prefer to provide more

immediate answers, make more subjective judgments.

And again, some people can be more systematic: they organize information in a

linear, sequential and cumulative way, don't like excessive or too varied

inputs, are activated even by low intensity stimuli. Others, on the other hand,

tend to be more intuitive: they love even complex and simultaneous

inputs, are activated by more intense stimuli, which they manage in real time.

Finally, there are people who are more cautious, who tolerate less risks

and the ambiguity of situations, compared to others who are more

willing to take risks and who tolerate any ambiguity of

contexts better. (Notice that the tolerance of ambiguity construct

points to important connections between purely cognitive

descriptors and a wider affective

dimension.)

There is no general theory of thinking/cognitive

styles, as investigations over the years have focussed on various

dimensions of styles, only partially correlated with each other (Note

3). It is therefore not easy to hypothesize direct correlations between

dimensions of cognitive styles: in other words, a certain caution is

needed in directly and automatically associating, for example,

analytical/systematic/reflective, on the one hand, and

global/intuitive/impulsive on the other, even if we could intuitively

suppose that a person with an analytical tendency may also exhibit

traits of a person with a systematic and/or reflective tendency (Note 4)

(Note 5)

3. Some important considerations

The terms we have used to identify individual differences in thinking styles

are absolutely neutral: there are no "better" or "worse" styles, let

alone "ideal" styles. In fact, all styles can be effective depending on the

situations, the contexts, the type of task one has to carry out. And knowing how

to use different styles, that is, being more flexible in the ways of

processing information, can in many cases be advantageous.

Not all people show extreme thinking styles: it is not common to find

people who are extremely analytical, or, on the contrary, extremely global.

Indeed, many tend to be in an intermediate position between the extremes we have

identified above, or to be more balanced than others. It is important

to recognize the uniqueness of each profile of thinking styles: each person is in

fact the bearer of personality dimensions that make him a unique individual.

Becoming more aware of one's thinking styles, as well as other dimensions of

one's personality, can enable us to get to know ourselves better, to understand

the reasons for some of our choices and behaviours, to identify our strengths

and weaknesses. This self-knowledge allows us to respond less automatically and

more consciously to the problems and challenges we face, increasing our

flexibility and our resilience.

4. Can movie preferences help us to learn more about our thinking

styles? An experimental questionnaire

Cinematic habits and attitudes, just like any other area of activity, can be

a source of information about an individual profile of thinking styles. Just as

personality traits, needs/motivations and beliefs/attitudes can affect

the uses we can put a film to (with particular reference to the

choice of particular film genres)(Note 6), our preferences in

choosing a film, our reactions during viewing and our interpretations

and evaluations after viewing can point to individual differences in

terms of our own personal cluster of thinking styles.

A preliminary experimental

questionnaire is offered below as a first step in surveying an area which has so

far

received no attention in the discussion of how movie

preferences and individual differences interact. The questionnaire is

structured in three parts. Part 1 is a collection of personal data on

movie preferences, based on the responses to 40 items ("statements")

that describe ways of interacting with and reacting to the cinematic

experience. Part 2 is the data processing stage, linking the given

responses to four continua of thinking styles dimensions (analytical vs

global, reflective vs impulsive, systematic vs intuitive, and tolerant

vs intolerant of ambiguity and risk). Finally, Part 3 asks the

respondents to evaluate the results of the questionnaire by relating

them to their own perceptions and opinions, thus inviting them to use

such results not as ultimate answers but as a starting point for further

reflection and discussion. This final part is important as the

questionnaire is conceived as a springboard to a progressively more

finely tuned description of one's own personal profile.

N.B. To answer the questionnaire you can use a pdf version that you can download

and/or print here.

QUESTIONNAIRE ON MOVIE PREFERENCES AND THINKING STYLES

The following questionnaire will explore our thinking styles,

i.e. the ways in which we process information in our minds. These styles vary from person to person

to a greater or lesser extent, and have important consequences for the decisions

we make and the ways we behave.

Some people may tend towards an analytical style: they prefer to start

from the parts to get to the whole, like to consider details, reason logically,

willingly focus on the differences between things. Others, on the other hand,

may tend towards a global style: they start from an overall vision and

from the general context, organize the information more simultaneously, find it

easy to make a synthesis, focus more willingly on the similarities between

things.

People also differ in their tendency towards reflectivity: more

reflective people

carefully consider facts and possible options, make more objective judgments,

require longer processing times. Others are more impulsive: they make

decisions based on sensations and essential information, prefer to provide more

immediate answers, make more subjective judgments.

And again, some can be more systematic: they organize information in a

linear, sequential and cumulative way, don't like excessive or too varied

inputs, are activated even by low intensity stimuli. Others, on the other hand,

tend to be more intuitive: they love even complex and simultaneous

inputs, are activated by more intense stimuli, which they manage in real time.

Finally, there are people who are more cautious, who tolerate less risks

and the ambiguity of situations, compared to others who are more

willing to take risks and who tolerate any ambiguity of

contexts better.

Cinematic habits and attitudes, just like any other area of activity, can be

a source of information about an individual profile of thinking styles. Keep in mind that any questionnaire of

this type can only give you a general indication of your profile and should not

be taken as a rigid and definitive "portrait" of some dimension of your

personality - in other words, not a point of arrival but a starting point for

further explorations. At the end of the questionnaire you will therefore be

asked to observe the results critically and to use your knowledge of your

behaviours, habits, attitudes, etc., to change or refine what appears to be your

own personal profile. Sharing and discussing the questionnaire and its results

with others is also highly recommended.

Choose the answer that best represents you.

Remember that there are no right or wrong answers!

PART 1

Decide how each of the following statements applies to you personally. Circle

the number in the appropriate column.

|

|

This is just like me

|

This is a bit like me

|

This is definitely

not like me

|

|

1. To "get in touch" with a film I need some time and to see different

scenes.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

2. I don't like movies that end in a completely unexpected way.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

3. I can't stand films at a very slow pace.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

4. I feel the need to understand why a character behaves in a certain

way.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

5. I don't like movies where there are several intertwining stories.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

6. I dislike movies (for example, crime/thrillers) where you have to pay

attention to clues and details.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

7. I like movies where what counts are action and movement.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

8. I appreciate films that invite reflection and discussion.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

9. I like characters to be well defined from the start.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

10. I watch a movie even if I have read a bad review.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

11. I don't like those plots where the end presents

some unresolved

points.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

12. I appreciate movies where you have to pay close attention to the

details of individual scenes.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

13. I like movies that keep giving me strong emotions.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

14. I like to focus on individual characters rather than the overall

plot.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

15. I tend to judge a character or get a good idea of her/him from the

very first scenes.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

16. I prefer films whose director and/or actors/actresses I know well

and appreciate.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

17. I don't like films with too complex plots, in which you have to

follow even the smallest details.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

18. If a movie ends in an ambiguous or unclear way, I'm still glad I saw

it.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

19. The first impressions I get of a character or situation are very

important to me.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

20. I prefer movies with a plot that develops clearly and logically.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

21. I'm not happy if I haven't been able to fully understand all the

developments of the plot.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

22. I like movies whose genre is clear, for example a comedy, a

drama, a n action movie ...

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

23. I prefer films in which, in addition to feeling emotions, one must

also reflect.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

24. If someone gives me a negative opinion of a movie, I'm unlikely to

go and see it.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

25. At the end of a film it is easy for me to say what its overall

meaning is.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

26. I quickly get a feel for the characters and how the story will

unfold.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

27. When I choose a film I don't give much weight to the name of the

director and/or actors/actresses.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

28. Before judging a character I expect to see her/him in action in many

scenes.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

29. I get easily carried away by the emotions of the story as a whole.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

30. I prefer movies with lots of action and lots of movement.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

31. I'm more involved in the story as a whole than in individual scenes.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

32. I appreciate movies with an ending that surprises me.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

33. I like movies whose plot develops gradually, step by step.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

34. I notice and appreciate details such as costumes, sets, colours ...

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

35. I prefer films in which the personality of characters is clearly

described.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

36. I listen carefully to dialogues and monologues to better understand

characters.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

37. I find it easy to guess how the plot of a film will develop.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

38. I appreciate a film as a whole, without paying attention to

particular aspects such as acting, sets, music, etc.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

39. I accept certain characters even if their personality or role in the

film are not entirely clear.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

40. I like movies that give me strong emotions.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

PART 2

For each statement fill in one or two squares depending on your answers,

always starting from the centre. Don't fill in any squares if you chose "0" as

an answer.

For example:

-

if for the analytical style in statement

12

you have circled number

1,

fill in the first square on the relevant line.

-

if for the global style in statement

6 you have circled number

2, fill in the first two squares on the relevant line.

|

STATEMENTS

|

ANALYTICAL

|

<------> |

GLOBAL |

STATEMENTS |

|

12

14 21 34 36

|

□

□

□

□ □ □ □ □ □ ■

|

|

■

■

□ □ □ □ □ □ □ □

|

6

17 25 31

38 |

|

STATEMENTS |

THINKING STYLES |

STATEMENTS |

|

|

ANALYTICAL

|

<----> |

GLOBAL |

|

|

12 14 21 34 36 |

□

□ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □

|

|

□

□ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ |

6 17 25 31 38 |

|

REFLECTIVE |

<----> |

IMPULSIVE |

|

1 4 8 23 28

|

□

□ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □

|

|

□

□ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ |

3 7 13 29 30 |

|

SYSTEMATIC |

<----> |

INTUITIVE

|

|

5 9 20 33 35

|

□

□ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □

|

|

□

□ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ |

15 19 26 37 40 |

INTOLERANT of ambiguity and risk

|

<----> |

TOLERANT of ambiguity and risk

|

|

2 11 16 22 24 |

□

□ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ |

|

□

□ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ |

10 18 27 32 39 |

PART 3

Think about the results and, if you can, discuss them with someone: do you agree

with the results of the questionnaire?

□ YES, because (give examples of your behaviors, habits, preferences, attitudes

...)

...……………………………………………………………….…………………………………..................................

□ NO, because (give examples of your behaviors, habits, preferences, attitudes

...)

..…………………….………………………………………………………………………………..……………............

□ Did you find this questionnaire useful? Do you think you have discovered

something new or interesting?

............................................................................................................................................................................

5. Multiple intelligences

A particular way of describing individual

differences takes into account the concept of intelligence. Intelligence has

often been considered (and is still very much is) as

-

innate, i.e. something "given" at birth, and

therefore not subject to the influences of cultural contexts;

-

stable, i.e. unchangeable through time;

-

general, i.e. made up of just one single factor

which remains basically the same when applied to different domains;

-

measurable, i.e. quantifiable on the basis of

tests (the well-known IQ (or "intelligence quotient"), which refers to the

"norm" or the "average" level of a population, usually assigned the value of

100 - implying that people are more or less intelligent than the "average"

if they score, respectively, more or less than 100 on an intelligence test).

This "traditional" view of intelligence has been

severely criticized in the past few decades, and other concepts of

"intelligence" have been put forward. The most famous of the "new" models is

probably due to psychologist Howard Gardner (1983, 1999), who rejects intelligence as a

single factor and identifies a number of different intelligences. According to this view, each

individual carries a different combination of

intelligences, which are not just the result of inborn, genetic potential,

but are also affected by the cultural contexts in which people grow up - different

cultures may value different intelligences and thus affect the individual

"profile" of each of their members.

Gardner has identified a number of intelligences,

which are best described in his own words (Note 7):

- Linguistic intelligence is the capacity to use language, your native

language, and perhaps other languages, to express what's on your mind and to

understand other people. Poets really specialize in linguistic intelligence,

but any kind of writer, orator, speaker, lawyer, or a person for whom

language is an important stock in trade highlights linguistic intelligence.

- People with a highly developed

logical-mathematical intelligence understand the underlying

principles of some kind of a causal system, the way a scientist or a

logician does; or can manipulate numbers, quantities, and operations, the

way a mathematician does.

- Spatial intelligence refers to the ability to represent the spatial

world internally in your mind - the way a sailor or airplane pilot navigates

the large spatial world, or the way a chess player or sculptor represents a

more circumscribed spatial world. Spatial intelligence can be used in the

arts or in the sciences. If you are spatially intelligent and oriented

toward the arts, you are more likely to become a painter or a sculptor or an

architect than, say, a musician or a writer. Similarly, certain sciences

like anatomy or topology emphasize spatial intelligence.

- Bodily kinesthetic intelligence is the capacity to use your whole

body or parts of your body—your hand, your fingers, your arms—to solve a

problem, make something, or put on some kind of a production. The most

evident examples are people in athletics or the performing arts,

particularly dance or acting.

- Musical intelligence is the capacity to think in music, to be able to

hear patterns, recognize them, remember them, and perhaps manipulate them.

People who have a strong musical intelligence don't just remember music

easily—they can't get it out of their minds, it's so omnipresent. Now, some

people will say, "Yes, music is important, but it's a talent, not an

intelligence." And I say, "Fine, let's call it a talent." But, then we have

to leave the word intelligent out

of all discussions of

human abilities. You know, Mozart was damned smart!

- Interpersonal intelligence is understanding other people. It's an

ability we all need, but is at a premium if you are a teacher, clinician,

salesperson, or politician. Anybody who deals with other people has to be

skilled in the interpersonal sphere.

- Intrapersonal intelligence refers to having an understanding of

yourself, of knowing who you are, what you can do, what you want to do, how

you react to things, which things to avoid, and which things to gravitate

toward. We are drawn to people who have a good understanding of themselves

because those people tend not to screw up. They tend to know what they can

do. They tend to know what they can't do. And they tend to know where to go

if they need help.

- Naturalist intelligence designates the human ability to discriminate

among living things (plants, animals) as well as sensitivity to other

features of the natural world (clouds, rock configurations). This ability

was clearly of value in our evolutionary past as hunters, gatherers, and

farmers; it continues to be central in such roles as botanist or chef. I

also speculate that much of our consumer society exploits the naturalist

intelligences, which can be mobilized in the discrimination among cars,

sneakers, kinds of makeup, and the like. The kind of pattern recognition

valued in certain of the sciences may also draw upon naturalist

intelligence.

So each person carries a different "combination" of intelligences

- note

that the following image (Fig. 2 - Note 8) gives "equal weight" to all

intelligences, but this is clearly a theoretical illustration - the "pie" for

each individual would show a unique combination.

Fig. 2

From this perspective, the evaluation of intelligence (or intelligences)

should answer, more than the question "How intelligent are you?", the

much more stimulating and productive question, "How intelligent are

you?"

|

|

As was done with thinking styles, a preliminary

experimental questionnaire is offered below as a first step in surveying

how movie preferences can offer an insight into an individual's personal

and unique cluster of intelligences. Like the questionnaire on thinking

styles, the one below is structured in three parts. Part 1 is a

collection of personal data on movie preferences, based on the responses

to 64 items ("statements") that describe ways of interacting with and

reacting to the cinematic experience. Part 2 is the data processing

stage, linking the given responses to the eight kinds of intelligence

described by Gardner. Finally, Part 3 asks the

respondents to evaluate the results of the questionnaire by relating

them to their own perceptions and opinions, thus inviting them to use

such results as a starting point for further

reflection and discussion. Once again, this final part is important as the

questionnaire is conceived as a springboard to a progressively more

finely tuned description of one's own personal profile.

N.B. To answer the questionnaire you can use a pdf

version which you can download and/or print here.

QUESTIONNAIRE ON MOVIE PREFERENCES AND MULTIPLE

INTELLIGENCES

It has been argued that intelligence is not a

general factor but rather a combination of different intelligences, each

of them applying to different areas of human experience. Psychologist

Howard Gardner has

described such intelligences in the following way:

- Linguistic intelligence is the capacity to use language, your native

language, and perhaps other languages, to express what's on your mind and to

understand other people. Poets really specialize in linguistic intelligence,

but any kind of writer, orator, speaker, lawyer, or a person for whom

language is an important stock in trade highlights linguistic intelligence.

- People with a highly developed

logical-mathematical intelligence understand the underlying

principles of some kind of a causal system, the way a scientist or a

logician does; or can manipulate numbers, quantities, and operations, the

way a mathematician does.

- Spatial intelligence refers to the ability to represent the spatial

world internally in your mind - the way a sailor or airplane pilot navigates

the large spatial world, or the way a chess player or sculptor represents a

more circumscribed spatial world. Spatial intelligence can be used in the

arts or in the sciences. If you are spatially intelligent and oriented

toward the arts, you are more likely to become a painter or a sculptor or an

architect than, say, a musician or a writer. Similarly, certain sciences

like anatomy or topology emphasize spatial intelligence.

- Bodily kinesthetic intelligence is the capacity to use your whole

body or parts of your body—your hand, your fingers, your arms—to solve a

problem, make something, or put on some kind of a production. The most

evident examples are people in athletics or the performing arts,

particularly dance or acting.

- Musical intelligence is the capacity to think in music, to be able to

hear patterns, recognize them, remember them, and perhaps manipulate them.

People who have a strong musical intelligence don't just remember music

easily—they can't get it out of their minds, it's so omnipresent. Now, some

people will say, "Yes, music is important, but it's a talent, not an

intelligence." And I say, "Fine, let's call it a talent." But, then we have

to leave the word intelligent out

of all discussions of

human abilities. You know, Mozart was damned smart!

- Interpersonal intelligence is understanding other people. It's an

ability we all need, but is at a premium if you are a teacher, clinician,

salesperson, or politician. Anybody who deals with other people has to be

skilled in the interpersonal sphere.

- Intrapersonal intelligence refers to having an understanding of

yourself, of knowing who you are, what you can do, what you want to do, how

you react to things, which things to avoid, and which things to gravitate

toward. We are drawn to people who have a good understanding of themselves

because those people tend not to screw up. They tend to know what they can

do. They tend to know what they can't do. And they tend to know where to go

if they need help.

- Naturalist intelligence designates the human ability to discriminate

among living things (plants, animals) as well as sensitivity to other

features of the natural world (clouds, rock configurations). This ability

was clearly of value in our evolutionary past as hunters, gatherers, and

farmers; it continues to be central in such roles as botanist or chef. I

also speculate that much of our consumer society exploits the naturalist

intelligences, which can be mobilized in the discrimination among cars,

sneakers, kinds of makeup, and the like. The kind of pattern recognition

valued in certain of the sciences may also draw upon naturalist

intelligence.

(http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/sept97/vol55/num01/The-First-Seven.-.-.-and-the-Eighth@-A-Conversation-with-Howard-Gardner.aspx)

Our "movie watching" habits, just like any

other area of activity, can be a source of information about our own

"intelligence pie". The following questionnaire will help you do just this. Please note

that any such a questionnaire can only give you a general indication of your own

profile - it should not be taken as a rigid, definitive "portrait" of your

intelligences or your personality. This is why, at the end of the questionnaire,

you will be asked to look at the results in a critical way and to use your

knowledge of your behaviours, habits, attitudes, etc., to change or better

refine what appears to be your own personal profile.

Sharing and discussing the questionnaire and its results with others is

also highly recommended.

Choose the answer that you feel most comfortable with.

There are no right or wrong answers!

PART 1

Decide how each of the following statements applies to you personally. Circle

the number in the appropriate column.

|

|

This is just like me

|

This is a bit like me

|

This is definitely

not like me

|

|

1. I prefer to watch a movie together with other

people (relatives, friends, etc.).

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

2. I appreciate accurate and detailed historical

settings in a movie.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

3. I often want to read a novel from which a film has

been made.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

4. I often listen to music from movie soundtracks.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

5. I like films that take little for granted and

instead invite us to speculate about what will happen in the story.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

6. I like films in which the forces of nature (e.g.

sea, wind, rain…) play an important role.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

7. I like films that provide strong sensations (e.g.

"scenes that “make your heart pound", or "a lump in the throat", or a

"shiver in the back" ...).

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

8. Before deciding to see a film, I ask the opinion

of others who have already seen it.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

9. I like to understand immediately where a film is

set, also through images of famous or characteristic places.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

10. I easily notice the characters’ regional accents

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

11. I don’t like films set in closed places, with

characters who prefer dialogue over actions and movements.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

12. I like listening to or watching presentations or

debates about a film.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

13. I like films that show extreme natural phenomena

(e.g. volcanic eruptions, monsoons, tornados, earthquakes…).

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

14. I am interested in what others think of a film I

have already seen.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

15. I don't like movies that don't have a clearly

explicit logical development.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

16. I like "on the road" films, in which characters

travel through very different places.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

17. I really like action films, where characters and

objects move often and quickly.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

18. I don't like movies with no musical soundtrack.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

19. I don't like movies that are totally fantastic or

set in unreal worlds.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

20. I like films "that make you dream", which carry

me to situations and places that may be very far from reality.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

21. I like biographical films describing the life of

scientists and their discoveries.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

22. I remember quite precisely films that somehow

moved or even upset me.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

23. After watching a movie, I like to discuss it with

others.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

24. I think that images are much more important

dialogues in a movie.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

25. I prefer films that take place in real natural

settings rather than films shot in artificial sets.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

26. I like films that are totally or partially spoken

in a regional dialect, even if I may miss a few words or phrases.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

27. I think watching a film is a very personal

experience, and I find it difficult to share it with others.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

28. I easily recognize the intonation with which a

character in a film expresses emotions or meanings (for example, when a

character expresses irony, sarcasm, contempt, admiration, etc.).

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

29. I like documentaries that illustrate the life of

people, even not famous ones, who have faced and solved problems and who

tell and explain their experience.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

30. The so-called "film-puzzles" (in which, for

example, the logical or temporal links are not immediately

understandable, or there are unusual or bizarre developments in the

story ...) stimulate me and challenge me to seek explanations.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

31. I really appreciate films that show the

relationship between men and animals..

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

32. I like “sports” films, which highlight the

physical and athletic qualities of the characters.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

33. I share on the Internet (Facebook, Instagram,

etc.) my judgments or opinions on the films I have seen.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

34. I like films that also address environmental

issues.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

35. I like documentaries that illustrate the works of

painters, sculptors, architects.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

36. I like films in which the dialogue plays a

decisive role (e.g. scenes in a courtroom, political debates,

conversations in a group of friends or in a couple ...).

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

37. While watching a movie, I like to recognize songs

or pieces of music that I know.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

38. I like documentaries that describe how scientific

or technological problems have been solved.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

39. I often compare characters and events in a film

with my personal life and experience.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

40. I like watching foreign films with Italian

subtitles.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

41. I like very eventful scenes, e.g. a chase between

cars or people.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

42. I like films, like detective stories, in which

you have to carefully observe the details to understand the development

and the final solution.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

43. I often take the initiative to go to the cinema

with others, or to see a movie together at home.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

44. I really like going to the cinema or watching a

movie at home even if I am alone.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

45. I look at the end credits of a movie to see what

kind of songs or music were used.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

46. I appreciate colours and how they are used in a

film.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

47. I like films that look like video games, in which

I almost take part in the action shown on the screen.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

48.

I really like “nature” documentaries.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

49. I often read movie reviews.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

50. I don’t really like films set in closed places,

with characters who prefer dialogue over actions and movements.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

51. After seeing a film

which moved me, I often think

about it.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

52. I often recommend a movie that I liked to other

people.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

53. I look carefully at the interiors in which a film

takes place (for example, the look of a flat, how it is furnished, and

other details such as paintings, ornaments, etc.).

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

54. I like films based on literary or theatrical

works.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

55. I like films "that make you think", that is, that

invite me to reflect on the characters and the story.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

56. I enjoy a scene from a movie more if it is

accompanied by music.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

57. I pay attention to how the actors use their

bodies, e.g. through gestures, facial expressions, use of hands ...

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

58. The great natural spaces (e.g. the prairies in

westerns, the jungle, the oceans or the mountains in adventure movies,

the beaches in certain comedies or dramas…) attract my attention a lot.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

59. I like films in which new technologies play an

essential role.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

60. I like animated films, especially when they use

unusual and original shapes, colours and images.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

61. I think music in a film is very important.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

62. I carefully observe the locations in which a film

takes place.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

63. I like to see a movie based on a novel I have

read so that I can compare the two versions.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

|

64. I often talk about the movies I have seen with

other people.

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

PART 2

For each statement fill in one or two square(s) according to your answer,

starting on each line from the first square on the left. Do not fill in any

squares if your answer is “0”.

For example, if for the linguistic

intelligence in statement No. 3 you circled “2”, fill in the first two squares:

|

LINGUISTIC

|

3

12 26

36 40

49 54

63

|

■ ■ □ □ □ □ □

□ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □

|

|

INTELLIGENCE

|

STATEMENTS

|

|

|

LINGUISTIC

|

3

12 26

36 40

49 54

63

|

□ □ □ □ □ □ □

□ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □

|

|

LOGICAL-MATHEMATICAL

|

5

15 19

21 30

38 42

59

|

□ □ □ □ □ □ □

□ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □

|

|

VISUAL-SPATIAL

|

2

9 16

24 35

46 53

60

|

□ □ □ □ □ □ □

□ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □

|

|

MUSICAL

|

4

10 18

28 37

45 56

61

|

□ □ □ □ □ □ □

□ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □

|

|

INTER-PERSONAL

|

1

8 14

23 33

43 52

64

|

□ □ □ □ □ □ □

□ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □

|

|

INTRA-PERSONAL

|

20

22 27

29 39

44 51 55

|

□ □ □ □ □ □ □

□ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □

|

|

BODILY-KINESTHETIC

|

7

11 17

32 41

47 50

57

|

□ □ □ □ □ □ □

□ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □

|

|

NATURALIST

|

6

13 25

31 34

48 58

62

|

□ □ □ □ □ □ □

□ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □

|

PART 3

Look at the table above: do you agree with your results?

□

YES, because (try to mention any of

your behaviours, habits, preferences …)

..…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

and/or

□

NO, because (try to mention any of

your behaviours, habits, preferences …)

..……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

|