Individual differences in cinema audiences

Luciano Mariani

info@cinemafocus.eu

© 2025 by Luciano

Mariani, licensed under CC

BY-NC-SA 4.0

Notes:

- A

pdf version

of this Dossier is available.

- The symbol

![]() means that the video is only available directly on YouTube.

means that the video is only available directly on YouTube.

1. Introduction

"The ability to gauge someone’s personality simply by examining their favorite films might be disconcerting to some, but it comes one step closer to answering the age-old question of whether we really are what we consume." (Note 1)

It is an obvious fact of life that people are different, in a great number of ways. Films, too, are vastly different. Difference, or, in other words, variety, is an essential feature of both natural and human life - what makes it both terribly complex and extremely fascinating. As part of this variety, it is easy to admit that different people like different kinds of films, which is to say that films cater for a range of individual preferences.

The fact that films are "consumed" in very different ways is reflected in viewers' individual and group reactions, so that the same movie can be considered not just as generically "good" or "bad", but also as "exciting" or "depressing", "beautifully shot" or "incoherent", and so on. For example, Irréversible (by Gaspar Noé, France 2002) garnered the following user reviews at IMDb (International Movie Database):

"One of the most disturbing and confronting movies ever made"

"Stick with it - not enjoyable, but admirable"

"Visceral, shocking, groundbreaking genius"

"Brilliant!"

2. Ways to approach individual differences

Individual differences can be studied from several perspectives, starting from the psychological one; and films, too, can be differentiated, most notably by assigning them to a range of film genres (from comedy to drama, from western to musical). The relationship between individual differences and types of films is significant, and has accordingly been explored for a range of possible interactions, which can give rise to several interesting questions:

a) perhaps the most common, and indeed the oldest, link is a purely commercial/financial one: How can cinema cater to a variety of audiences? How can a movie appeal to as many viewers as possible, so as to provide the biggest possible box-office returns? These commercial considerations have more recently been revamped and boosted by new marketing strategies, which employ relatively recent technologies (e.g. algorythms) to track the viewing habits of individuals in order both to create extensive information databases for production and distribution companies and to provide personalized feedback to viewers - the question then becoming, how can individual preferences be matched with suitable viewing suggestions?

b) a related avenue of research, which extends beyond the "mere" marketing interest, is the way movie preferences can help explore human personality: What can choices in entertainment media (more specifically, films) tell us about viewers' individual differences? In this perspective, we start from film choices and arrive at the individual differences that they imply: film preferences can help to understand individual profiles;

c. reversing this question, one can also research the ways personality affects film choice: How can personality factors predict movie preferences? In this case we start from individual differences and arrive at the choices that are made in terms of kinds of entertainment media (more specifically, films): individual profiles can help to understand film preferences;

d) finally, the relationship between individual differences and cinema has for a long time been considered (mainly, if not exclusively) in terms of the effects that certain kinds of films, or rather, certain types of film content (e.g. violence. sex) can have on different kinds of audiences: How are people affected by what they see and hear? Can film content cause or prompt some people (more than others) to change their beliefs, attitudes and, ultimately, behaviour?

This paper is concerned mainly with the questions raised in b) and c) above, although the relevance of both these avenues of exploration to marketing strategies (i.e. a) above) is clearly very high (at times, indeed, becoming of overwhelming, even exclusive interest). In the same way, the (positive or negative) impact of movies on individuals (i.e. d) above) still remains an important effect of both traditional and newer kinds of entertainment media.

3. The "cinematic experience"

3.1. Different behavioural, psychological and social patterns

To provide concrete examples of individual differences, we may consider the nature of the "cinematic experience", i.e. what viewers bring to the vision of a film, how they structure this vision, and what kind of outcomes they expect to gain. The results of a survey (Note 2) highlighted how such an experience is multi-dimensional as several factors were identified, with useful and interesting insights into the different ways in which people experience their relationship with a movie. Such factors can be summarized as follows:

1. specialty downloader: downloading movies from the Internet has become a common behaviour among film buffs. This involves a very active disposition, which includes watching a wide range of movies, including foreign ones, activating subtitles if necessary, and also listening to movie soundtracks;

2. loses plot line: the degree of involvement in watching a movie can vary greatly, with some people having problems in following the film plot, which can lead to avoiding movies with elaborate plots;

3. social media commentator: with more and more films made available in different formats and through a variety of electronic devices, a large number of people find that the cinematic experience does not end with the film's end - they continue to discuss the movie, especially through social networks, blogs, chats. This does not necessarily imply an exclusive "home vision", since real film buffs are often keen to see movies in theatres, as soon as they are released;

4. revisiting narrative: the widespread availability of movies also means that they can be watched over and over again, perhaps changing the device (e.g. a laptop computer, a tablet, a smartphone); this can also imply a preference for fiction films rather than documentaries;

5. personal reflection: in connection with no. 3 above, some people

are readier than others to enjoy films that can be used to reflect on the

film's themes, relating them to their own experience and perhaps allowing

the discovery of hidden aspects of their personality;

6. style and dialogue: some people are more interested than others in the style and techniques involved in producing a film (e.g. mise-en-scène, camera movements, editing) and/or in its narrative strategies, including the role of characters and the verbal part of narration (e.g. dialogues, first-person narration);

7. evaluating film versus advertisements: with the increasing amount of advertisements presented not just before or after a film, but even within it, it is only natural that people may differ in their reactions towards such a practice, which can also impact on the overall evaluation of the viewing experience once it is over;

8. realistic stars: a film's cast can be a strong motivation to choose a film, especially if stars feature prominently;

9. controlling viewer: this factor identifies people who like to control the flow of vision, e.g. by pausing the film, re-watching parts or stopping watching it altogether (all options that are available in the home vision but obviously not in theatres);

10. mood immersion: some viewers are particularly keen on choosing movies that match their own mood. The feeling of "total immersion" can be heightened in the theatrical experience of a movie, when being in a completely dark room and in relatively complete isolation can provide a different quality of the vision itself.

The results of this research (Note 3) are also noteworthy because they highlight, not only differences at audience level, but also the different aspects that viewers take into account when they refer to their film preferences. As a matter of fact, when people refer to "movies" they may be referring to one ot more of the following film features: film-inherent (e.g. plot, characters, aspects of cinematography like camera movements lighting, editing, etc.), film-external (e.g. film reception, awards gained, critical appraisal) and the effects of film use (both in terms of the resources demanded of/activated by audiences, like the need for deeper cognitive efforts to understand and appreciate a film, and in terms of the effects that the film itself can have on its viewers, like entertainment, personal growth, social awareness or commitment). In other words, the relationship between movies and their audiences can be described by referring to the features of movies, to the viewing situation (e.g. in a theatre rather than through a streaming platform at home, all alone or with friends, which also impacts on the social aspect of movie-going) and finally to the realm of viewers' individual differences.

In addition, we must take into account the obvious fact that movie evaluation can take place

a. before exposure (i.e.before viewing), when choice of a movie can be affected by, e.g. critical acclaim, box-office success, nominations and awards, or simply word-of-mouth recommendations;

b. during exposure (i.e. while watching a movie), when positive and negative involvement can be affected by prior expectations: if we watch violent scenes in a film which we did not expect to show violence, we may decrease our level of involvement or even stop watching, especially if we dislike violent films in general and/or consider them as morally unacceptable; or, to give another example, we may start watching a movie mainly with a view to gather information on a topic but find ourselves moved or excited by what we see, thus changing the quality of our involvement and evaluation;

c. after exposure, when the overall evaluation of a movie depends on a host of factors, which have to do with the features of the movie itself but also, and most importantly, with our attitudes towards specific film genres and specific film features. For example, if a movie is congruent with our prior attitudes and expectations, we are likely to evaluate it in more positive terms than if it does not meet what we consider to be important movie features (like ways of acting, shooting, editing, etc.). In this respect, film genres are important factors to consider, since they provide viewers with rather specific expectations (towards, e.g. what can be expected from a western or a comedy) which provide the benchmark for subsequent evaluation: "This is not what I expected from a horror movie" or "This is not what I expected from a Jim Carrey film" are common judgments which betray a clash between what movies can offer viewers and what viewers themselves bring to the watching situation. In particular, film expertise, or the individual viewer's knowledge and experience of movies and movie-making, can greatly impact on the comprehension and appreciation of movies, especially if a movie is challenging because, e.g. it requires the processing of complex information or greater aesthetic skills for artistic appreciation.

3.2. Various aspects of a movie impact different viewer reactions

From the start, our discussion of individual differences in film preferences must take into account the various aspects of a movie which viewers may find more or less important when evaluating a movie. A research survey (Note 4) isolated eight main factors which viewers may find useful when providing an evaluation of a movie. You will notice that some of these factors concern the content of a movie (e.g. plot, characters) while others concern its form or style (e.g. use of film language like shooting and editing) as well as external aspects (like the information concerning a particular movie and the effects movies can have on audiences):

1. Story verisimilitude or degree of realism, i.e. the fact that the movie reflects (contemporary) reality;

2. Story innovation, or the degree to which the story can be considered new or original;

3. Cinematography, or the cinematic techniques used to produce a film (like framing, camera movements, editing);

4. Special effects, which are really part of cinematography but, with the advent of digital technologies, are impacting in ever increasing or pervasive ways on film production;

5. Recommendations, or, more generally, external resources, like film criticism, used to evaluate a movie;

6. Innocuosness, or the absence of unpleasant features (e.g. with respect to sex or violence);

7. Light-heartedness, or the degree to which a movie can provide entertainment and also act as a way to escape boredom or monotony;

8. Cognitive stimulation, or the degree to which a movie can provide "food for thought", i.e. opportunities for learning and reflecting.

3.3. Film genres and their cognitive and emotional appeal

Another important set of considerations regarding the "cinematic experience" concerns the fact that a film genre can be one of the strongest factors affecting the choice (or rejection) of a particular movie by particular people. People like or dislike certain genres and can therefore base their decision to watch a movie on their genre preferences. We will address the relationship between film genres and personal preferences in a later section, but, by way of preliminary remarks, it is interesting to report the results of a study (Note 5) which attempted to find out if some general factors could explain the specific attractiveness of different media genres (not just films but also music, books and television). The results point to some fascinating aspects of genres which we will take up again later. Five major factors were identified which were common to several music, book, television and movie genres, which we list below with their specific reference to (very general) film genres:

a. Communal (romance, family): lighthearted, uncomplicated, popular, focussing on people and relationships;

b. Aesthetic (foreign, classic): creative, abstract, cultural, challenging;

c. Dark (horror, cult): intensity, edginess, hedonism;

d. Thrilling (action, science fiction): adventure, suspense, fantasy;

e. Cerebral (documentary): factual information about people, places and other aspects of the real world.

These factors were correlated with various demographic variables: gender was most strongly related to the factors, followed by intelligence, education, age and ethnicity. Some of the most interesting results can be summarized as follows: females and people with low levels of education scored high on the Communal factor; people with high edcation levels, abstract reasoning ability and females scored high on Aesthetic; young people, males and Hispanics scored high on Dark; men more than women and less educated people scored high on Thrilling; older people and males scored high on Cerebral.

When correlated with personality variables (examined in more detail below), the most intriguing results can be summarized as follows: Communal was found related to psychological characteristics like pleasant, lighthearted, unadventurous, uncomplicated and relationship-oriented; Aesthetic to creative, calm, introspective and in touch with emotion; Dark to defiant, reckless and immodest; Cerebral to enterprising, innovative, intellectual, self-assured and detail oriented.

These results are mentioned here only as a preliminary example of how specific features of movie genres can cater for and appeal to some specific groups of people on the basis of individual differences.

3.4. Other aspects of the "cinematic experience"

Individual differences, however, cannot be reduced to demographic and personality variables only, although these factors are of the utmost impirtance. Other variables are worth taking into consideration. Situational variables may greatly affect entertainment preferences: for example, being in a certain mood, like being tired or stressed rather than relaxed, may favour the choice of light-hearted entertainment not requiring high levels of attention or cognitive effort; boredom or restlessness may favour the choice of thrilling, exciting media; the need for information on a specific topic may favour the choice of documentaries or factual media; and, generally speaking, certain media can be chosen because they offer emotional stimulation when needed. This means that, alongside personality traits, which are relatively stable over time and for a certain individual, we need to consider mental states, i.e. temporary moods which can change over time and point to differences not just between and among individuals but also, importantly, within a single individual.

In the same vein, the demands of social contexts can affect media preferences. For example, some social groups are defined mainly in terms of their preferred media (music, movies, etc.), and people who share such preferences have been found to share psychological characteristics, too - not to mention the fact that media preference can be used to define one's own personality and communicate it to others (with social media offering powerful opportunities to do so), with the additional remark that sharing media preferences can affect the quality of interpersonal relationships (e.g. within a family or between friends or romantic partners).

3.5. Viewers as active agents, not passive recipients

The concepts expressed so far point to a major feature of film audiences, i.e. that fact that viewers are not simply receiving what they see and hear as passive entities, but are instead active agents in choosing (or rejecting), comprehending, appreciating and evaluating the content and form of the screen images and sounds. As we will explore in more depth in the next section, it is important to go beyond considering just how media affect people (e.g. in terms of violent behaviour) to explore which kinds of individual differences affect the choice (or rejection) of media - or in simpler terms, study what people do with the media instead of what the media do to people.

4. Differences in processing a film

4.1. The viewing process

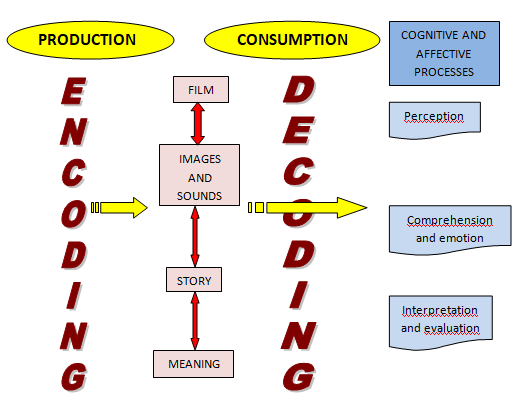

Before considering the various ways in which individual differences in movie preferences can be identified and discussed, it is useful to briefly describe the process involved in viewing a film (Fig. 1 below)(Note 6).

Fig. 1

This process starts with a film's production by, e.g. a studio, when the people responsible for creating the movie encode, i.e. convey, the film's meaning through a particular use of film language. The product is the film itself, which must then be decoded by viewers - viewers need to retrieve the meaning which was originally encoded. This is not a mechanical or automatic activity, since viewers do not simply produce a mirror image of the original meaning: they bring with them beliefs, attitudes, past experiences, motivations and other personal attributes which do not necessarily match those of the original "creators" of the film. In other words, the meaning of the film as decoded by its viewers may be (and in most cases actually is) different in a variety of ways from the "original, intended meaning". The film consists of images and sound, which give form and structure to a story, which is imbued with meaning(s). Viewers are not passive recipients of all this - indeed, they are actively involved (even if at possibly different degrees of consciousness) in a process which starts with their perception of the images and sound. Watching a movie means using and elaborating the input from the screen, and in so doing viewers set in motion both cognitive mechanisms (to understand what they see and hear: story, characters, etc.) and emotional mechanisms (which trigger their emotional reactions). Through comprehension and emotion, viewers are able to interpret what they now perceive as the film's meaning and eventually evaluate the viewing experience (e.g. as an enjoyable and/or meaningful one). It goes without saying that the outcome of this process may not be what the original creators had envisaged, because people who produce the film (encoders) are different from the people who view it (decoders): viewers have their own world views, and will therefore produce different meanings in accordance with such views. What is most interesting for our discussion is that viewers themselves are different in a variety of ways, so that there will be as many final interpretations and evaluations of a film as there are viewers.

4.2. Case study: Thelma & Louise - and a touch of cultural differences

To illustrate how different viewers interpret and evaluate a film's meanings as a result of the process described in Fig. 1, we can consider audience reactions to a film that has sparked off considerable debate, Thelma and Louise (by Ridley Scott, USA 1991).

Reactions, mainly based on the themes of gender and violence towards women, were broadly divided into three groups (Note 7). One group, who positively evaluated the film, liked the female characters (played by Geena Davis and Susan Sarandon) who were perceived as both funny and disturbing, and, while not directly quoting feminist issues, were sympathetic with the plight suffered by them. Another group, who evaluated the film negatively, found that, faced with irresponsible and stupid males, the two women were led to criminal acts. However, contrary to the legitimate expectation that women would like the film while men wouldn't, many male critics appreciated the film and several female critics didn't. The most negative reaction was from male critics who found that the picture of male characters was flawed and biassed beyond reasonable limits. A third group also judged the film negatively, but on different grounds. They saw the movie as a bad example of false feminism, whereby women, while reacting to men's violence, actually took up typically masculine roles in order to carry out their revenge. In other words, the female characters were accused of using traditional masculine weapons (like the use of guns) instead of relying on (again traditional but also stereotyped) feminine means (like reflecting and discussing the relevant issues).

Different viewer interpretations were also found in the years following the initial release of the film. A year later, for example, there was not much difference between women and men who liked the film - men in particular thought that the film conveyed negative images of male characters but still enjoyed other features of the movie, like the drama behind the events, the action sequences and the beautiful settings. A couple of decades later, by the end of the 2000s, there was no noticeable difference between the film's appreciation by women and men, with the latter now ceasing to find male characters negatively portrayed: this was also a response to the changes in time towards the roles of women in action films, with heroines now appearing nearly as often as men as determined, even ruthless characters.

All in all, women still seem to like the film slightly more than men, but the most interesting difference concerns the process of viewer identification with characters. While women usually identify strongly with the female characters, men, although not feeling threatened by the female violence portrayed in the film, do not readily identify with Thelma and Louise, but can definitely identify with the "positive" male characters (mainly the sympathetic ones like the detective played by Harvey Keitel or Louise's boyfriend played by Michael Madsen).

Women identifying with the female characters often quote two dramatic sequences from the movie, the one where Thelma shoots the man trying to rape Louise in a parking lot towards the beginning of the film (see Video 1 below) and the heartbreaking finale, with the two women consciously refusing to surrender to the police and driving off a cliff (see Video 2). Here we have an interesting example of the interaction between (cognitive) comprehension and (affective) emotion in determining the overall interpretation and evaluation of a film's meanings (see Fig. 1 above): although some viewers perceive a clear link between these two scenes (the ending as a result of the sexual assault), many female viewers report feeling angry during the first sequence but feeling "free" during the ending, which is not felt as a suicidal decision but as a way to "break free" from an oppressive (male) society and a refusal "to give in" by reaffirming the value of friendship.

Video 1 Video 2

A final note may serve as a reminder that individual differences are not just psychological constructs but are also affected by a cultural dimension. The TV soap opera Dallas (created by David Jacobs - see the trailer of Season 1 in Video 3 below) ran for years and was a huge worldwide success, suggesting that the "values" and "messages" conveyed by the series had a sort of "universal" appeal. However, this was not the case. Surveys (Note 7) showed that Arabs and Moroccan Jews appreciated the story events, and particularly the strong emphasis on family relationships, from a moral standpoint. Americans and Israelis liked the psychological motivations and strong feelings driving the actions of individual characters. Russians, on the other hand, were particularly critical of the consumerist messages conveyed by the story, characters and overall production of the series.

Video 3

5. Individual differences, movie differences and the problems in identifying and describing them

"Given the seemingly infinite number of factors affecting viewers’ responses‚ it is clearly a very difficult task to explain why one viewer screams in terror during a horror film while the next shrugs in indifference‚ or why one viewer sobs uncontrollably during a tear-jerker while another yawns from boredom." (Note 8)

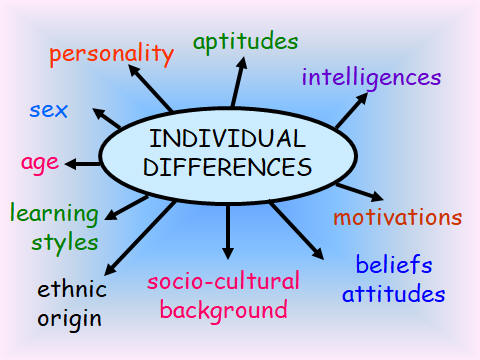

People can be different in a very wide variety of ways (Fig. 2 below) and one of the main problems in studying individual differences is how to approach such variety and which factors to concentrate on. Some factors have to do with biological aspects (e.g. age, sex), others with social and cultural aspects (e.g. sociocultural background, ethnic origin). Generally speaking, the basic concept used to start identifying differences is often a psychological one - personality, which in most cases can be considered an "umbrella" term, i.e. a complex structure of factors which are defined in different terms according to different personality theories. Indeed, several factors highlighted in Fig. 2 could be assumed to be part of an overall picture of personality: however, several of such factors (e.g. intelligence(s), motivation, beliefs and attitudes, aptitudes) have also been explored as independent concepts - a fact which will be reflected in the following discussion about film preferences. This preliminary "map" of individual differences, however, runs the risk of underestimating the basic fact that an individual's profile as a person is a sum of all the interactions that constantly take place between and among all the "mapped" factors; or, in other words, that biological, psychological, social and cultural factors can and should be considered separately only temporarily, and for purposes of easier study - always keeping in mind the structural unity of each individual human being.

Fig. 2

Another preliminary observation which needs to be mentioned is the fact that differences can be detected not just between and among individuals, but also within each person according to different times and circumstances: for example, personality studies often establish a difference between traits (stable characteristics of an individual) and states (changing moods or temporary conditions). This is an important fact to keep in mind, since it points to the relative, and not absolute, character of the choices that people make when deciding to watch a movie - decisions that are the results of both stable personality traits and contingent, changing circumstances.

A similar question arises when trying to identify how to differentiate films, although in this case we can rely on the well-established tradition of classifying films into genres. Indeed, most studies dealing with individual movie preferences assume film genres as the reference variable: the assumption here is that people can choose an action rather than a sci-fi or musical film for reasons that have to do with their personality traits, and conversely, that a personality trait can predict the preferences in film genres. Genres are thus convenient, and relatively easy-to-use, labels to identify the differences between movies, but even in this case a word of warning is in order, for at least three reasons. First, although one can easily detect and describe the ways in which, e.g. a thriller is different from a comedy, a single movie can exhibit features of different genres: "action" scenes are not just the exclusive domain of action movies, and romantic tones are not confined to "sentimental" movies or melodramas. Second, genres have never been watertight compartments: if on the one hand they tend to ensure stability and coherence, for example in their themes and stylistic choices, on the other hand they undergo changes to meet changing audience expectations: this happened, for instance, with westerns in the "New Hollywood" of the '60s and '70s and with musicals all along their history. Third, traditional distinctions between and among movies, which in the past have greatly helped to relate a particular film to a rather specific audience (like "women's films" in the Hollywood tradition), have in more recent times become blurred, as movies tend to incorporate aspects of different genres: thus today we can talk of dramedies to refer to the blending of comedy and drama. This poses an important question when trying to decide what features of a particular film can motivate an individual person's choice. If genres are still the basic concept to be taken into consideration when discussing film preferences, the choice of particular movies can depend on factors that go beyond "genre", thus complicating the issue.

All in all, both personality descriptions and film genre identification are not exempt from critical aspects, which suggest care in the interpretation and evaluation of results from research on individual differences and film preferences.

6. Personality

6.1. The "Big Five" model

"In mainstream personality research, personality is broadly conceptualized in terms of largely stable and biologically influenced individual differences that characterize an individual’s typical patterns of behavior across different situations." (Note 9)

The value of personality as a concept expressed in these terms is its predictive value, i.e. the fact that it implies how a person will probably behave under certain circumstances - in our case, what her/his movie preferences will be. Among the various models which attempt to describe personality structure, the most widely used for the purpose of investigating individual differences in movie choice is the so-called Big Five Model (Note 10), which posits five main traits: Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness. These terms need some clarification, since they refer to meanings that may not always coincide with their usual, everyday uses; besides, these terms refer to tendencies rather than absolute values. Neuroticism, for example, does not refer to a pathological condition but to a propensity to a low emotional stability, which leads to the experience of negative emotions like anxiety, stress, pessimism (conversely, people with a low value of neuroticism are more emotionally stable). Extraversion refers to a tendency to enjoy the company of others and to be confident and outgoing, while introverts are shy, passive, reserved and likely to enjoy being alone or with a few selected friends. Openness denotes people who are intellectually curious, open to new experiences and creative, while people low in this trait prefer to remain within the boundaries of their knowledge and experience and are less prone to try out novelties. Agreeableness identifies people who are open to others, sensitive to others' feelings and ready to open up, while the opposite is true for disagreeable people, who may be arrogant and not so ready to consider other people's needs and emotions. Finally, people high on the Conscientiousness trait are responsible, reliable, capable of self-management and even ambitious; conversely, people low on this trait are less-focused on plans and initiative, may be disorganized and with less ambition and self-control.

These five traits can be investigated through self-report questionnaires, which are made up of a number of statements to which respondents are asked to react by choosing the degree to which they agree or disagree (this obviously assumes that people are consistent and can be trusted to provide accurate information, and that reported behaviours can predict future ones). An example for the Extraversion trait (and its reverse, Intraversion) might be:

| Disagree strongly 1 |

Disagree moderately 2 |

Disagree a little 3 |

Neither agree nor

disagree 4 |

Agree a little 5 |

Agree moderately 6 |

Agree strongly 7 |

2. I like to be on my own in my free time.

Sometimes statements are replaced by adjectives describing the trait (or its reverse), e.g. (Note 11):

I see myself as ...

1. extraverted, enthusiastic

2. reserved, quiet

or by a continuum between two opposites, where an individual profile can be established by choosing a position along this continuum, e.g. (Note 12):

(for Neuroticism) secure/calm <----------> unconfident/nervous

(for Extraversion) solitary/reserved <---------->outgoing/energetic

(for Openness) cautious/consistent <----------> curious/inventive

(for Agreeableness) cold/unkind <----------> friendly/compassionate

(for Conscientiousness) careless/easy going <----------> organized/efficient

6.2. Personality traits and film genres

Several studies report findings that point to a link between personality traits, as described by the "Big Five" model and film genres. For example (Note 13), Extraversion seems to be related for a preference for comedy and romance, and this is understandable, since extraverts like what these two genres usually abound in, i.e. meaningful connections with other people, with comedies providing the "lighter side" of these connections through dialogues, jokes, witty exchanges, etc.; Agreeableness, too, can point to a preference for romance, with its predominant focus on relationships, empathy and compassion (keeping in mind that women usually score higher in Agreeableness as well as Conscientiousness, a fact that will be taken up again in the section on sex and gender below); agreeable people, with their warm, kind approach, are also found to dislike horror movies. The link between Openness and documentaries and science fiction films comes as no surprise, since these are two genres that cater for intellectual curiosity, information seeking and processing, adventure and new experiences. Openness has also been found to be related to a preference for comedies, which may contain non-predictable, unconventional plots, and stimulating characters - a feature which is at least in part shared by fantasy films. Action films were also found to be chosen by people high on Conscientiousness, probably because such films are based on rather predictable plots and therefore appeal to people who prefer familiarity over novelty; this is also true for romantic films, which, by usually carrying positive, optimistic feelings can also appeal to people high on Neuroticism.

Another example of research results provided these links (Note 14):

| High | Low | |

| Openness | tragedy, neo-noir, independent, cult, foreign | war, romance, action, comedy |

| Conscientiousness | independent, adventure, science fiction | cult, animation, cartoons |

| Extraversion | drama, romance, comedy, action | animation, tragedy, neo-noir, science fiction |

| Agreeableness | adventure, romance, comedy, drama | parody, animation, neo-noir, cult, horror |

| Neuroticism | cult, tragedy, animation | adventure, independent, war |

Notice that while some links are intuitive, confirming what one would expect from people sharing the same personality traits, others are less obvious and are usually worthy of further research. Also notice that there is no one-to-one link between traits and film genres, as the latter can appeal to more than one trait.

This kind of research makes use of questionnaires designed to explore genre preferences (where people are asked to declare their preferences on a scale, e.g. between the two extremes of Dislike extremely to Like extremely), also by inviting them to quote one or more movies that they have enjoyed and asking them to assign these movies to a particular film genre from a list. A deeper insight can be gained by asking people to select what they consider the most important aspects of movies, choosing from a list (e.g. cinematography, score, acting, favourite actors, story/plot, humour, love, gore/violence, mystery/suspense, characters, positive and negative emotional impact, action, information/learning benefit), thus moving beyond the simple (and sometimes ambiguous) labels of "genres" (Note 15).

7. From personality to needs and motives to use films

Personality traits are assumed to influence behaviours (in our case, film choice) through complex psychological mechanisms. When people experience a particular mood (which, by definition, is transient and changeable), this gives rise to certain needs, which in turn activate corresponding goals, i.e. motives for the subsequent choices. This process is affected by personality traits (which, contrary to moods, are stable and persistent), which activate the evaluation of the available choices (e.g. "I like/dislike this" or "This is good/bad for me") and create the expectations that the final choice will provide the gratification, i.e. the satisfaction of the perceived need. For example, I may be bored and feel the need for some sort of novelty and excitement by watching a movie - my goal then becomes to find a suitable one. If I tend to be high on Extraversion, I will probably look for a movie that I know I might like (or that I assess as good for me) because it will provide me with positive sensations of excitement and fun - and that I expect will satisfy my need. Crucially, I now have a motive to choose a particular film use, for example "to seek sensation", which in turn will orient me to select a corresponding film genre (maybe an action movie, a thriller or a horror film). We can summarize this complex process by saying that personality traits predispose individuals to choose media (film genres) that are congruent with their transient moods.

In a nutshell, people use films to satisfy a need and reach a goal, which gives rise to a motive for watching, i.e. one (or more) film use(s) - activating the choice of a film genre. The whole process is affected by their personality traits.

Film uses cater for a wide range of motives, which can

be classified into three main areas of human activity: emotional

(catering for the need to experience and manage emotions); cognitive

(catering for the need to find out and process information); and social

(catering for the need to relate to others). Fig. 3 below summarizes the

relationships between personality traits, film uses and film genres.

|

PERSONALITY TRAITS |

MOTIVES FOR WATCHING

leading to FILM USES |

FILM GENRES |

|

Extraversion

Agreeableness

Conscientiousness

Neuroticism

Openness |

|

(e.g.)

..... |

|

Video 4 |

|

Video 5 |

Much research into the connections between personality and film uses has been of a commercial, rather than of an academic, origin. This comes as no surprise, since the information gathered with such research is of great use to film studios and streaming platforms, in their efforts to produce and distribute movies that cater for specific audiences, by discovering audiences' viewing patterns and customizing and personalizing the products on offer. Once correlations have been found between certain film uses/film choices and personality traits, this information can be used as predictive of similarity in movie preferences, greatly enhancing the precision of "suggestions" offered to viewers for further viewing experiences. This audience profiling powered by "recommendation engines" has been implemented for a considerable time, and high-tech companies are well aware of the issues at stake, as Steve Job happened to say a few years go:

“What the studios need to do is start embracing the front end of the

Algorithms are widely used to assist researchers in this enterprise, and Artificial Intelligence is already making such efforts more and more productive.

6. Sex, gender and age

"It is important that researchers also consider the role of viewers’ responses to and enjoyment of the content [of gender-stereotyped portrayals] because (1) entertainment fare is often targeted specifically to male vs. female audiences; and (2) differential viewing of media entertainment may serve to exacerbate sex role stereotyping and behavior differences." (Note 23)

Research has consistently proved that there are differences in film preferences between women and men (Note 24). However, the issues at stake here are complex, starting from the basic fact that biological sex (with opposition between male and female) interacts with gender (a socio-cultural construct, which allows more space for non-binary descriptions).

Some studies have shown that males definitely prefer action, crime and sex films over females, and the reverse is true for romantic, dramatic and historical films, with comedies, horror and fantasy films being slightly preferred by males over females: this reduced difference for comedies and fantasy movies can partly be explained by the "hybrid" nature of such films, which often show common features that do not focus so clearly on violence and relationships (Note 25), This points, once again, to the ambiguous nature of several film genres: action, crime and horror movies can differ widely with regard to the measure of violence shown, just as dramatic films can differ with regard to the measure of pathos, leading to variations within the same genre, and not just between or among different genres.

Some answers were also provided to the question whether females and males enjoying the same film genres also have similar personality traits. This appears to be the case (Note 25, with the exception of Openness: females (who do not generally favour action movies), were more open than males when found to like this film genre, and the reverse was true for romantic films (male fans were more open than females). This points to an interesting relationship betwen gender and personality.

However, it is even more interesting to examine the reasons why viewers expressed such preferences. For example, early research found that

"Generally‚ men responded that it was very “natural” for them to prefer action-packed films over romantic ones simply because they were of the “masculine” gender. In contrast‚ women responded that they preferred love stories because such films touched and moved their hearts‚ thus bringing out their “feminine” traits. Similarly‚ other studies have reported that females evidence greater fear and less enjoyment of frightening films than do males ... On the other hand‚ males report less involvement‚ interest‚ emotional responsiveness‚ and enjoyment of sad films or tear-jerkers than do females." (Note 26)

This is of the utmost importance because it points to

the fact that people hold stereotypical views about male and female

personalities (e.g. "females are more emotional, empathic and caring than

males"), and also report different reactions (sadness, fear and sometimes joy

for females, pointing to "affiliation" and "social contact"; anger for males,

pointing to "competition" and "self-assertion"). These stereotypes should also

make us alert to the fact that there are differences, not just between

people of the opposite sexes, buit also within each sex: in other

words, within a group, some women may be found to be, e.g. less

"sympathetic" than some men, and, conversely, some men may be found less

"competitive" than some women. These between sex and within sex

variations highlight the role of beliefs and attitudes in

shaping expectations as to the appropriate social behaviour

that women and men are supposed to exhibit; these expectations are internalized

and are consistent with the gender roles that they are expected to

perform - with the crucial consequence that. under some circumstances,

gender (and its stereotypes) may influence film preferences more or better

than simply biological sex. This means that some individuals will be

particularly sensitive (in positive and negative ways), e.g. to horror movies or

tear-jerkers, quite apart from their sex. The self-perception of gender

roles is therefore a most important factor in explaining people's emotional

reactions to movies, and consequently their stated film preferences. These

considerations add significant meaning and help to better understand the already

reported differences in film preferences (with the notable finding that

"gender roles have essentially no

influence on females‚ but have a very strong

influence on males" - Note 27).

As a general rule, when considering research results, one must also consider the possible impact of other variables, for instance age and cultural/ethnic origin, which may considerably have a mediation effect on the relationship between personality and film preferences. For example (Note 28), when considering three age groups (young - 25 and younger; middle - 26-49; older - 50 and above), interesting differences were observed regarding several film genres: dramatic films were chosen in much more significant ways by the Young compared to the other groups, while horror movies were least appreciated by the Older group; action and adventure films were definitely more a "Young" genre, but romantic films were chosen more by young females than by young males. Also, the Young group preferred recently released movie compared with the other groups. This has been tentatively explained in several ways: more recent movies exhibit more violence and special effects, which would make them more popular with young people; young viewers have not been exposed to different film styles and changes over the years (as older groups have); however, it is not simply that older viewers may be "nostalgic":

"A key determinant may be the continuous reactivation of the aesthetic filter that was operating at the time a movie was initially seen. This flexibility in stylistic shifts, leading to an appreciation of films from earlier film eras, would simply be unavailable to most younger filmgoers." (Note 29)

Changes In time were also noted: as male viewers age, they cite romantic films (an all-age preference for female viewers) as a favourite genre - and, more generally, the middle and older groups gradually show a decreased measure of difference between males and females.

7. Conclusion

As the previous paragraphs have shown, individual differences can be identified and described in several different ways, having recourse to a variety of psychological theories and to countless variables. This may give the impression that research is following such diverse approaches that comparison and, ultimately, synthesis is almost impossible. However, this also points to the very nature of individual differences: personal profiles are made up of a very complex network of relationships, and each profile is unique to a single individual. This does not mean that generalizations, i.e. descriptive trends and tendencies, cannot be realized, but it alerts us to the fact that, in the case of movie preferences as well as in most other cases, we need to rely on a variety of different, and in some cases alternative, ways of describing the way that individuals respond to their need for (and appreciation of) movies. In other words, the extremely wide range of research results outlined in this paper should be taken not as a sign of confusion, but rather as evidence that human behaviour defies simple explanations and calls for an open, critical and comprehensive approach.

Appendix

Two alternative ways of describing individual differences, which are not taken into consideration by the literature reviewed in this paper, are based on thinking styles (i.e. ways of processing information) and multiple intelligences (as opposed to the concept of a single general measure of intelligence). These two alternative approaches can be used in the exploration of movie preferences, adding a fascinating, if complex, perspective to the ones outlined above. Movie preferences can thus help in understanding yet other aspects of personality. The paper Movie preferences as a key to individual differences: Thinking styles and multiple intelligences provides a preliminary examination of the topic and offers pathways for future research.

Notes

1. Romans A. We Are What We Watch: Film Preferences and Personality Correlates, Oklahoma State University, p. 3. Also in The American Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Research, Volume 05, Issue 03, pp. 08-12.

2

3. Schneider F.M. 2017. "Measuring Subjective Movie Evaluation Criteria: Conceptual Foundation, Construction, and Validation of the SMEC Scales", Communication Methods and Measures, p. 4.

4. ibid., p. 15.

5. Rentfrow P.J., Goldberg R.N. & Zilca R. 2011. "Listening, Watching, and Reading: The Structure and Correlates of Entertainment Preferences", Journal of personality, 79(2), p. 231.

7. ibid., pp. 121-125.

9. Kaufman & Simonton, cit., p. 90.

10. ibid., p. 90.

11. A short version of a questionnaire measuring the Big Five personality factors using only 10 pairs of adjectives is the Ten-Item Personality Inventory (TIPI) in Gosling S. D., Rentfrow P. J. & Swann, W. B., Jr. 2003. "A Very Brief Measure of the Big Five Personality Domains", Journal of Research in Personality, 37, pp. 504-528.

12. Detailed references to research in this domain is offered, e.g. by Kaufman & Simonton, cit.; Treasa M.J. 2023. "Do We Watch What Matches our Personality? Movie Preferences and Personality", The International Journal of Indian Psychology, Volume 11, Issue 3, pp. 3801-3806; Kallias A. 2012. Individual differences and the psychology of film preferences, Department of Psychology, Goldsmiths College, University of London. This publication includes a Uses of Film Inventory (originally developed by Chamorro-Premuzic), a 50-item questionnaire following the self-report format here exemplified. See Chamorro-Premuzic T. & Furnham A. 2009. "Mainly Openness: The relationship between the Big Five personality traits and learning approaches", Learning and Individual Differences, 19 (4), 524-529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2009.06.004. Also see Dr. Chamorro-Premuzic's web page: What type of movie person are you? on the Psychology Today website.

13. Cf. Romans. cit., and Chausson, cit.

14. Cantador I. Fernández-Tobías I, Bellogín A, Kosinski M., Stillwell D. 2013. "Relating Personality Types with User Preferences in Multiple Entertainment Domains", Conference: Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on Emotions and Personality in Personalized Services (EMPIRE), p. 3.

15. Examples of such questionnaires can be found in Ronans, cit., pp. 16-18.

16. Cf. Note 12.

17. Cf. Mariani L. 2022. "Why do we pay to get scared?" The paradoxical lure of horror films", cinemafocus.eu

18. Beth Oliver M. "Individual differences in media effects", in Zillmann D., Bryant J. & Beth Oliver M. Media effects: Advances in theory and research, Taylor & Francis, Hoboken, p. 509.

19. Cf. Mariani, cit.

20. Beth Oliver M. & Raney A.A. 2011. "Entertainment as Pleasurable and Meaningful: Identifying Hedonic and Eudaimonic Motivations for Entertainment Consumption", Journal of Communication, 61, pp. 994.

21. Beth Oliver, cit., p. 517.

22.

Quoted in Palomba

A. 2020.

"Consumer

personality and lifestyles at the box office and beyond: How demographics,

lifestyles and personalities predict movie consumption"

23. Cf. Chausson, cit., p. 46.

24. Infortuna C., Battaglia, F. Freedberg, D. Mento, C. Zoccali, R. A. Muscatello, M. R. A. & Bruno, A. 2021. "The inner muses: How affective temperament traits, gender and age predict film genre preference". Personality and Individual Differences, 178, Article 110877. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110877

25. Cf. Chausson, cit.

26. ibid., p. 47.

27. ibid., p. 59.

28. Fischoff S., Antonio J. & Lewis D. 1998. "Favorite films and film genres as a function of race, age and gender", Journal of media psychology, Vol. 3, No. 1.

29. ibid., p. 21.