Playlists

|

Playlist Playlists |

|

Finali indimenticabili dalla storia del cinema Unforgettable endings from cinema history |

|

| Nota: E' disponibile una

versione

pdf di questo Dossier. |

Note: A

pdf version

of this Dossier is available. |

|

Versione italiana English version |

|

| Apriamo la nostra playlist con uno dei finali più famosi della storia del cinema. A qualcuno piace caldo è la storia di due musicisti (Jack Lemmon e Tony Curtis) che si travestono da donna per sfuggire a dei gangster, venendo così a conoscere la bella e sensuale Zucchero (Marilyn Monroe) - una storia che sembra fatta apposta per far intuire come andranno a finire le cose. Eppure, il geniale regista Billy Wilder ci stupisce fino all'ultima battuta di questo film, diventata ormai di culto. Mentre fuggono su un motoscafo, con la coppia Curtis-Marilyn seduta sul sedile posteriore, vediamo davanti a noi Lemmon accanto ad un vecchio magnate che si è innamorato di lei/lui e lo voule sposare. Lemmon fa di tutto per convincere il vecchiardo che il matrimonio non è possibile ... finchè, togliendosi la parrucca, esclama, con voce decisamente maschile, "Sono un uomo!" - al che il vecchio risponde sornionamente, "Beh, nessuno è perfetto". Sono le ultime parole del film, prima che compaia la dicitura "FINE", con una battuta fulminante quanto sorprendente, che non ammette repliche ... |

A qualcuno piace caldo/Some like it hot (di/by Billy Wilder, USA 1959) |

Our playlist opens with one of the best-known endings in the history of cinema. Some like it hot is the story of two musicians (Jack Lemmon and Tony Curtis) who disguise themselves as women to escape gangsters, thus getting to know the beautiful and sensual Sugar (Marilyn Monroe) - a story which seems to be created to let you understand how things will end. Yet, brilliant director Billy Wilder amazes us until the last line of this film, which has now become a cult. As they flee on a motorboat, with the Curtis-Marilyn couple sitting in the back seat, we see Lemmon in front of us next to an old tycoon who has fallen in love with her/him and wants to marry him. Lemmon does everything to convince the old man that marriage is not possible ... until, taking off his wig, he exclaims, in a decidedly masculine voice, "I'm a man!" - to which the old man slyly replies, "Well, nobody's perfect." These are the last words of the film, before the word "END" appears, with a fulminating and surprising joke, which does not allow for replies ... |

| Il

celeberrimo finale di Thelma & Louise ingloba in sè molti

significati: il breve viaggio-vacanza di due donne (Geena Davis e Susan

Sarandon), alla ricerca di un po' di libertà e di soddisfazione lontano

da mariti inappaganti, si è trasformato in un incubo, dopo che Louise ha

ucciso un uomo che tentava di violentare Thelma. Mentre il cerchio della

polizia si stringe attorno a loro, le due donne fanno ancora incontri

con uomini violenti, misogini e disonesti, e toccano con mano la

condizione femminile in un mondo dominato dai maschi. Ma per loro non

c'è posto in questo mondo, e, giunte alla fine sull'orlo del Grand

Canyon, decidono di non stare più al gioco perverso di una società

ingiusta e violenta - sancendo con un ultimo bacio la loro amicizia, che

è anche un toccante gesto di una preziosa solidarietà al femminile,

lanciano la loro auto nel vuoto. Ma il regista sceglie di non farci

vedere la loro fine, di "tenerle in vita" nonostante tutto: con un

fermo-immagine, l'auto rimane sospesa a mezz'aria, come ad indicare che

nemmeno la morte può scalfire i valori in cui Thelma e Louise hanno

voluto credere. |

Thelma & Louise (di/by Ridley Scott, USA 1991) |

The very famous finale of Thelma & Louise encompasses many meanings: the short vacation trip of two women (Geena Davis and Susan Sarandon), in search of a little freedom and satisfaction away from their unfulfilling husbands, turned into a nightmare after Louise killed a man who attempted to rape Thelma. As the police circle tightens around them, the two women still have encounters with violent, misogynistic and dishonest men, and experience the female condition in a world dominated by males. But for them there is no place in this world, and, having finally reached the edge of the Grand Canyon, they decide to no longer play the perverse game of an unjust and violent society - sanctioning their friendship with one last kiss, which is also a touching gesture of precious solidarity between women, they throw their car into the void. But the director chooses not to let us see their end, to "keep them alive" in spite of everything: with a freeze-frame, the car remains suspended in mid-air, as if to indicate that not even death can scratch the values in which Thelma and Louise wanted to believe. |

| Uno dei più celebri finali ad utilizzare il freeze frame

(o fermo-immnagine) si trova in I

quattrocento colpi, dove, dopo aver

assistito per tutto il film alle vicissitudini del giovane Antoine

(Jean-Pierre Léaud), lo

vediamo alla fine fuggire dal riformatorio dove è stato rinchiuso, e

cominciare a correre, correre, correrre ... attraveso i campi fino

a raggiungere il mare (che sappiamo non ha mai visto). E, sulla

battigia, dopo aver fatto qualche passo, Antoine si volta verso la

macchina da presa, che si avvicina a lui e lo fissa per sempre in un

primo piano "congelato": nel suo sguardo possiamo naturalmente

proiettare tutte le sensazioni che abbiamo provato nei suoi confonti

durante tutto il film, ma ciò che forse più colpisce in questo "fermo

immagine" è il significato simbolico: Antoine, alla fine, non ha

raggiunto la libertà, la sua corsa non lo ha portato ad una vera meta, e

tutte le incognite sul suo futuro rimangono dolorosamente per lui (nel

suo sguardo) e per noi (spettatori) aperte. |

I 400 colpi/Les 400 coups/The 400 blows (di/by François Truffaut, Francia/France 1959) |

One of the most famous endings to use the "freeze frame" can be found in

The

400 Blows, where, after witnessing the

vicissitudes of the young Antoine (Jean-Pierre Léaud) throughout the

film, we see him at the end escape from the reformatory where he was

confined, and start running, running, running ... through the fields

until he reaches the sea (which we know he has never seen). And, on the

beach, after taking a few steps, Antoine turns towards the camera, which

approaches him and fixes him forever in a "frozen" close-up: in his gaze

we can naturally project all the sensations we have experienced towards

him throughout the film, but what is perhaps most striking in this

"still image" is the symbolic meaning: Antoine, in the end, did not

reach freedom, his journey did not lead him to a real goal, and all the

unresolved facts about his future remain painfully (for him, in his

gaze) and for us (as the audience) open. |

| In uno dei primi film-chiave della "New Hollywood", e rimasto giustamente

famoso per il carattere di "rottura" che si andava profilando nel

sistema hollywoodiano, Il laureato narra le vicende di

Benjamin (Dustin Hoffman), un ragazzo che, al termine del college,

senza nessuna idea chiara sul suo futuro, viene sedotto da un'amica di

famiglia (Anne Bancroft), anche se poi di fatto si innamora della figlia

di quest'ultima, Elaine (Katharine Ross). Determinata a superare in fretta lo

scandalo, la famiglia di Elaine organizza il suo matrimonio con un

altro ragazzo, e Benjamin, messo al corrente della cosa, corre

disperatamente verso la chiesa dove Elaine ha appena pronunciato il

fatidico sì. Benjamin però non si arrende, strappa la ragazza dalle mani

dello sposo, blocca la porta della chiesa (con una croce!) e scappa con

Elaine a bordo di un autobus. Nella sequenza finale, i due si siedono

sorridenti in fondo all'autobus, ma la loro espressione si fa

subito incerta: quando Benjamin guarda Elaine, lei sta guardando

altrove, pensierosa; quando Elaine guarda Benjamin lui sta sorridendo,

ma in una direzione diversa. Di fatto, non si guardano, ma guardano,

ciascuno per conto suo,

davanti a sè, come davanti al futuro, con insicurezza se non con vera

apprensione. E tutto ciò mentre ritorna il motivo musicale (The sound of silence,

di Simon & Garfunkel), che aveva aperto il film e che aveva

accompagnato i momenti più tristi della storia, e che ora

suggella con il "silenzio" la situazione finale dei personaggi ... |

Il laureato/The graduate (di/by Mike Nichols, USA 1967) |

In one of the first key films of the "New Hollywood", and rightly famous for the innovative productions that were emerging in the Hollywood system, The Graduate tells the story of Benjamin (Dustin Hoffman), a boy who, at the end of college, without any clear idea about his future, is seduced by a family friend (Anne Bancroft), even if he then actually falls in love with the latter's daughter, Elaine (Katharine Ross). Determined to overcome the scandal quickly, Elaine's family organizes a wedding with another boy, and Benjamin, made aware of the matter, runs desperately towards the church where Elaine has just been married. Benjamin does not give up, snatches the girl from the groom's hands, blocks the church door (with a cross!) and escapes with Elaine aboard a bus. In the final sequence, the two sit smiling at the back of the bus, but their expressions immediately become uncertain: when Benjamin looks at Elaine, she is looking away, thoughtful; when Elaine looks at Benjamin, he's smiling, but in a different direction. In fact, they don't look at each other, but they look in front of themselves, as if in front of the future, with insecurity if not with real apprehension. And all this while the musical motif returns (The sound of silence, by Simon & Garfunkel), which had opened the film and which had accompanied the saddest moments of the story, and which now seals the final situation of the characters with ... "silence". |

| Nel cinema italiano resta celeberrimo il finale di Il sorpasso, storia dell'incontro tra un trentaseienne cialtrone e sbruffone, Bruno (Vittorio Gassman) e un timido studente universitario, Roberto (Jean-Louis Trintignant), che viene coinvolto dal nuovo amico in una serie di incontri, tutti all'insegna della superficialità e della faciloneria di Bruno, in un mondo (quello del boom economico dell'Italia dei primi anni '60) ormai indirizzato verso il consumismo e una messa in crisi dei valori tradizionali. Il "viaggio" dei due uomini si concluderà in modo tragico, e sarà proprio Roberto a morire nell'incidente d'auto. Quando la polizia chiede a Bruno, "Era un suo parente?", lui risponde, "Si chiamava Roberto ... Il cognome non lo so ... L'ho conosciuto ieri mattina", chiudendo così, in modo anonimo, una vicenda che per tutto il film non ha mostrato che un vuoto di fondo, che è individuale quanto collettivo. |

Il sorpasso/The easy life (di/by Dino Risi, Italia/Italy 1962) |

In Italian cinema the finale of The easy life remains very famous: it is the story of the encounter between a thirty-six-year-old scoundrel and braggart, Bruno (Vittorio Gassman) and a shy university student, Roberto (Jean-Louis Trintignant), who is involved with his new friend in a series of meetings, all under the banner of Bruno's superficiality and carelessness, in a world (that of Italy's economic growth in the early 1960s) now directed towards consumerism and a crisis of traditional values. The "journey" of the two men will end tragically, and it will be Roberto himself who dies in the car accident. When the police ask Bruno, "Was he a relative of yours?", he replies, "His name was Roberto ... I don't know his last name ... I met him yesterday morning", thus anonymously closing a story which throughout the film showed only a basic emptiness, which is individual as well as collective. |

| Di tutt'altra natura, e aperto al futuro e a quello che potrebbe accadere dopo la fine del film, è il finale di Via col vento. Dopo aver seguito i due protagonisti principali, Rhett (Clark Gable) e Rossella (Vivien Leigh) nel corso degli anni e del succedersi degli eventi, nell'ultima scena lui è determinato ad andarsene "per trovare la pace" ed è sordo alle implorazioni di lei. E' qui che viene pronunciata una delle battute più celebri e fulminanti della storia del cinema, quando lui, di fronte alle pressanti richieste di lei ("Se te ne vai, che sarà di me? Che farò?") risponde disinvolto e quasi sprezzante, "Francamente, me ne infischio". Rossella, disperata e annientata dal dolore, cade sfinita, ma sente una voce fuori campo che le ricorda quasi ossessivamente il senso che la sua famiglia aveva sempre avuto per la piantagione di cotone Tara: "La terra è la sola cosa che duri, la sola cosa per cui vale la pena di lottare ... Tara, Tara, Tara". Rossella allora si rialza, e, con una nuova determinazione nello sguardo, pronuncia un'altra celeberrima battuta: "A casa, a casa mia. E troverò il modo per riconquistarlo ... Dopo tutto, domani è un altro giorno". E, sullo sfondo di un tramonto infuocato vediamo la sagoma nera di Rossella stagliarsi contro il cielo, mentre l'altrettanto celebre motivo musicale che ci ha accompagnato per tutto il film chiude trionfante questo melodramma dalle tinte così forti. |

Via col vento/Gone with the wind (di/by Victor Fleming, USA 1939) |

Of a completely different nature, and open to the future and to what could happen after the end of the film, is the ending of Gone with the Wind. After following the two main protagonists, Rhett (Clark Gable) and Scarlett (Vivien Leigh) through the years and the turn of events, in the last scene he is determined to leave "to find peace" and is deaf to her pleas to stay with her. It is here that one of the most famous and fulminating lines in the history of cinema is uttered, when he, faced with her pressing requests ("If you leave, what will become of me? What will I do?") replies casually and almost contemptuously, "Frankly, my dear, I don't give a damn." Scarlett, desperate and destroyed by pain, falls exhausted, but hears a voice-over that almost obsessively reminds her of the sense that her family had always had for the Tara cotton plantation: "The earth is the only thing that lasts, the only thing worth fighting for…Tara, Tara, Tara". Scarlett then stands up, and with a new determination in her gaze, she pronounces another famous line: "Home, my home. And I'll find a way to win him back ... After all, tomorrow is another day". And against the backdrop of a fiery sunset we see Scarlett's black silhouette against the sky, while the equally famous musical motif that has accompanied us throughout the film triumphantly closes this magnificent melodrama. |

| Un altro celeberrimo finale conclude Come eravamo. Nel film abbiamo seguito la tormentata storia d'amore tra uno scrittore dotato di talento ma disponibile ai compromessi (Robert Redford) e un'ebrea comunista, determinata e dall'incrollabile impegno sociale e politico (Barbra Streisand), tra gli anni '30 e gli anni '50 del secolo scorso. Nonostante il profondo legame che li unisce, i valori e gli ideali in questione finiranno per far saltare l'unione della coppia. Nel toccante finale, i due si ritrovano per caso, dopo anni di separazione, in una strada di New York: lui è diventato uno scrittore di successo, lei continua ad impegnarsi, nel clima di guerra fredda, per il pacifismo. Inutile dire che questo incontro è all'insegna della nostalgia del passato, del rimpianto per ciò che non è potuto essere, delle speranze frustrate. Entrambi i protagonisti hanno formato nuove coppie, e lei sta crescendo la figlia che ha avuto da lui - è evidente che si amano ancora, ma le circostanze rendono una riunione ormai impossibile. Dunque un finale "infelice", in cui però il sapore dolce della nostalgia e del rimpianto ha, agli occhi degli spettatori, una valenza molto più sfumata, un senso di straziante agro-dolce (che il tema musicale, corrispondente alla canzone di grande successo interpretata dalla Streisand, sottolinea in modo inequivocabile). E la determinazione di lei nel proseguire negli anni il suo impegno politico, costituisce un elemento di ammirazione che in qualche modo tempera quello che poteva essere un finale solo melodrammatico. |

Come eravamo/The way we were (di/by Sydney Pollack, USA 1973) |

Another famous endingcomes as the finale of

They way we were. In the film we followed the tormented love story

between a talented but politically unengaged writer (Robert Redford) and

a determined communist Jew with an unwavering social and political

commitment (Barbra Streisand), between the 1930s and the 1950s. Despite

the deep bond that unites them, the values and ideals in question will

end up destroying the union of the couple. In the touching ending, the

two meet by chance, after years of separation, in a street in New York:

he has become a successful writer, she continues to work for pacifism in

the Cold War climate. It goes without saying that this meeting is marked

by nostalgia for the past, regret for what could have been, frustrated

hopes. Both protagonists have formed new couples, and she is raising the

daughter she had from him - it is evident that they still love each

other, but circumstances make a reunion now impossible. Therefore this

is an "unhappy" ending, in which, however, the sweet taste of

nostalgia and regret has, in the eyes of the spectators, a much more

nuanced value, a sense of heartbreaking bittersweet (which the musical

theme, corresponding to the very successful song performed by Streisand,

underlines unequivocally). And her determination to continue her

political commitment over the years constitutes an element of admiration

that somehow tempers what could only have been a melodramatic ending. |

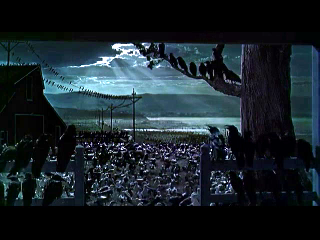

| Un finale

carico di tensione e di disperazione, al limite dell'horror puro,

conclude Gli uccelli. In un paesaggio devastato e ormai preda dei pennuti, un

gruppetto di sopravvissuti riesce ad andarsene via in auto, lasciando

dietro di sè un mondo sconvolto dall'apocalisse, ormai preda di queste

forze della natura che incarnano la loro ribellione contro gli umani.

L'ultima inquadratura trasmette un'angoscia quasi insostenibile, con il

campo quasi interamente occupato da queste migliaia e migliaia di

uccelli, che sembrano ora in attesa di poter sferrare un nuovo, decisivo

attacco. Non c'è redenzione e speranza, la

trama non si chiude e la narrazione neppure, soffocata dall'orrore di

quanto abbiamo visto in tutto il film, e che il finale non fa che

sottolineare ancora di più. |

Gli uccelli/The birds (di/by Alfred Hitchcock, USA 1963) |

An ending full of tension and despair, on the verge of pure horror, awaits us at the end of The Birds. In a devastated landscape and now prey to birds, a small group of survivors manage to leave by car, leaving behind a world devastated by the apocalypse, now prey to these forces of nature who embody their rebellion against humans. The last shot conveys an almost unbearable anguish, with the field almost entirely occupied by these thousands and thousands of birds, which now seem waiting to launch a new, decisive attack. There is no redemption and no hope, the plot does not close and neither does the narration, suffocated by the horror of what we have seen throughout the film, and which the ending only underlines even more. |

| Ladri di biciclette, capolavoro del neo-realismo italiano, mette in scena, nel desolante panorama socio-economico del secondo dopoguerra, la drammatica e amara vicenda umana di un padre cui viene rubata la bicicletta, strumento indispensabile per il suo lavoro, e che tenta a sua volta di rubarne una: bloccato dalla folla, viene poi lasciato libero, il tutto davanti alle lacrime del figlio. Padre e figlio camminano fianco a fianco, in mezzo alla folla accorsa in seguito al tentato furto, e nei loro sguardi spaventati e disperati non possiamo che "tenere aperti" i nostri occhi, e dunque il finale del film, che non può chiudersi con la fine di una storia che è invece una tragedia che continua. Che cosa faranno padre e figlio, se si procureranno una nuova bicicletta, come troveranno il modo di sopravvivere ... non è dato sapere. La loro storia continua ... |

Ladri di biciclette/Bicycle thieves (di/by Vittorio De Sica, Italia/Italy 1948) |

Bicycle thieves, a masterpiece of Italian neo-realism, staged, in the desolate socio-economic panorama of the post-war period, the dramatic and bitter story of a father whose bicycle, an indispensable tool for his work, is stolen and who in turn tries to steal one: blocked by the crowd, he is then set free, all in front of his son in tears. Father and son walk side by side, in the midst of the crowd that has gathered following the attempted theft, and in their frightened and desperate looks we can only "keep our eyes open", as well as the film's ending, which cannot close with the end of a story that is instead a tragedy that continues. What father and son will do, if they get a new bicycle, how they will find a way to survive ... is not known. Their story continues ... |

| E.T.

l'extra-terrestre si chiude con

la celebrazione di ideali (di amicizia, fraternità, tolleranza e

accettazione della diversità), e in cui l'addio tra il piccolo

Elliot e E.T. si conclude con il veicolo che si porta via E.T.,

disegnando nel cielo una sorta di arcobaleno - un finale che potrebbe

essere visto come molto sentimentale o melodrammatico (anche se il

sentimentalismo di Spielberg non è fine a se stesso, ma si riscatta

riuscendo a toccare le profondità della mente umana). |

E.T. L'extra-terrestre/E.T. The extra-terrestrial (di/by Stephen Spielberg, USA 1982) |

E.T. the extra-terrestrial ends with the celebration of ideals (of friendship, fraternity, tolerance and acceptance of diversity), and in which the farewell between little Elliot and E.T. ends with the vehicle carrying E.T. home, drawing a sort of rainbow in the sky - an ending that could be seen as very sentimental or melodramatic (although Spielberg's sentimentality is not an end in itself, but is able to touch the depths of the human mind). |

| Il rilancio della romcom negli anni '90 è evidente in un film come Pretty woman, con l'incontro tra un miliardario un po' maschilista ma tutto sommato bisognoso di affetto (Richard Gere) e una prostituta un po' volgare ma di gran cuore (Julia Roberts). E' una favola moderna, che nel finale vede il Cavaliere-Principe Azzurro letteralmente scalare un edificio come se fosse la torre di un castello, per ritrovare e liberare la bella principessa lì rinchiusa. E, ancora una volta, l'happy ending smaschera la consapevolezza di Hollywood dei meccanismi narrativi sottostanti. Sulle note celeberrime e travolgenti della "Traviata" (lei si è nel frattempo appassionata all'opera lirica), quando lui chiede, "E che succede dopo che lui ha scalato la torre e salvato lei?", lei risponde, "Che lei salva lui" - ma una voce fuori campo, mentre la macchina da presa si allontana dal bacio finale e la colonna sonora riprende il motivo dominante del film, ci avverte, "Benvenuti a Hollywood! Qual è il vostro sogno? Tutti vengono qui. Questa è Hollywood, la città dei sogni. Alcuni si avverano, altri no, ma continuate a sognare, questa è Hollywood ... si deve sognare, perciò continuate a sognare!". Come dire: il cinema serve a sognare, e i sogni servono a dimenticare la realtà. |

Pretty woman (di/by Garry Marshall, USA 1990) |

The relaunch of the "romcom" in the

1990s is clear in a film like Pretty Woman, with the meeting between a somewhat chauvinist

billionaire but all in all in need of affection (Richard Gere) and a

somewhat vulgar but big-hearted prostitute (Julia Roberts). It is a

modern fairy tale, which in the finale sees the Knight-Prince Charming

literally climb a building as if it were the tower of a castle, to find

and free the beautiful princess locked up there. And, once again, the

happy ending exposes Hollywood's awareness of the underlying narrative

mechanisms. On the famous and overwhelming notes of the "Traviata" (she

has in the meantime become passionate about opera), when he asks, "And

what happens after he has climbed the tower and saved her?", she

replies, "That she saves him" - but a voice-over, as the camera pans

away from the final kiss and the soundtrack picks up on the film's

dominating motif, warns us, "Welcome to Hollywood! What is your dream?

Everyone comes here. This is Hollywood, the city of dreams. Some come

true, some don't, but keep dreaming, this is Hollywood ... you have to

dream, so keep dreaming!". As if to say: cinema is for dreaming, and

dreams are for forgetting reality. |

|

Nei film

"meta-cinematografici" è il film a proporsi come elemento centrale della

storia: il film, cioè, svela il suo meccanismo,

rompe la "quarta parete" che tradizionalmente è riservata alla macchina

da presa (e dunque agli spettatori) e ci fa entrare, "da

protagonisti" all'interno del film stesso. Nei finali di questi

film spesso assistiamo ad una vera e propria apertura del set

cinematografico: gli attori e le attrici che hanno interpretato i

personaggi ora compaiono come le persone vere che sono, e dunque si

rompe l'incanto dello spettacolo: l'illusione si scioglie nella realtà,

e quello che ora ci viene mostrato non è più il prodotto finale di un

lavoro a cui come spettatori siamo fisicamente estranei, ma il processo

stesso di creazione di quel prodotto. Film dunque di rottura, di crisi, in cui è il cinema stesso ad essere messo in discussione. Ad esempio, 8 1/2 non a caso è incentrato sulla crisi professionale ed esistenziale del suo protagonista, un regista: una crisi di ispirazione che non è solo una questione privata ma diventa la crisi stessa della natura del cinema, del fare film, delle funzioni a cui il cinema può assolvere e della relazione tra regista, film e pubblico. Lo straordinario finale si svolge sul set del film, ma non per realizzare riprese quanto per "mettere in mostra" tutta la "macchina" del cinema, dalle impalcature agli interpreti, che sfilano tutti, insieme al regista, al suono di una marcetta da circo (la famosissima composizione del Maestro Nino Rota). |

8 1/2 (di/by Federico Fellini, Italia/Italy, USA 1963) |

In "meta-cinematic" films

it is the film that presents itself as the central element of the story:

that is, the film reveals its mechanism, breaks the "fourth wall" which

is traditionally reserved to the camera (and therefore to the audience)

and lets us enter, "as protagonists" within the film itself. In the

endings of these films we often witness a real opening of the film set:

the actors and actresses who have played the characters now appear as

the real people they are, and therefore the spell of the show is broken:

the illusion melts into reality, and what we are now shown is no longer

the final product of a work to which as viewers we are physically alien,

but the very process of creating that product. Such films have therefore a disruptive nature and question the nature and function of cinema itself. For example, 8 1/2 is, not by chance, focussed on the professional and existential crisis of its protagonist, a director: a crisis of inspiration which is not only a private matter but becomes the very crisis of the nature of cinema, of making films, of the functions which cinema can serve and of the relationship between director, film and audience. The extraordinary ending takes place on the set of the film, but not to shoot but rather to "show off" the whole "machine" of cinema, from the scaffolding to the performers, who all walk past, together with the director, to the sound of a circus march (the very famous composition by Maestro Nino Rota). |