Dossiers

|

Dossier Dossiers |

|

La narrazione cinematografica: dalla storia all'immagine |

Film narration: from story to image |

|

Note: - E' disponibile una versione pdf di questo Dossier. - Alcuni video da YouTube, segnalati dal simbolo - Il simbolo |

Notes: - A pdf version of this Dossier is available. - Some YouTube videos, featuring the - The symbol |

|

Indice 5. La durata e la frequenza degli eventi 6. I meccanismi di causa ed effetto 9. Il punto di vista: chi sa che cosa, e quando?

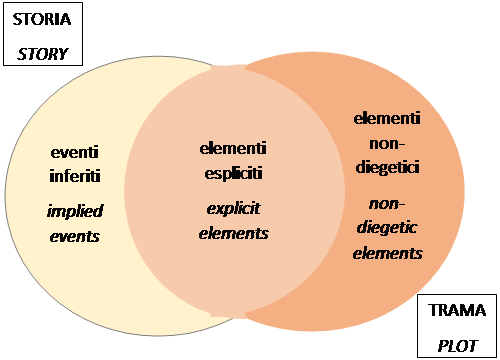

Vedere un film è una delle molteplici possibilità che possediamo di fruire di storie. Dal racconto di un amico delle sue vacanze estive alla cronaca di un avvenimento sportivo, dalla semplice barzelletta al più complesso romanzo storico, siamo immersi continuamente in un mondo di storie, che raccontiamo e che ci vengono raccontate. Lo storytelling è ormai diventato, oltre che una tecnica didattica e un metodo di analisi della realtà, una condizione esistenziale, arricchita e trasformata ormai in esperienza multimediale continua e quasi ossessiva. I film raccontano sempre storie - o almeno, lo spettatore si aspetta di vedere e sentire una storia, e si avvicina alla fruizione di un film con un'"attrezzatura mentale" che gli consente (e forse lo obbliga) a (ri)costruire nella sua mente ciò che vede e sente (si veda il Dossier Aspettative, atteggiamenti e strategie). Anche il film più "sperimentale", anche il film che dichiaratamente si rifiuta di raccontare una storia, è comunque soggetto almeno al tentativo, da parte dello spettatore, di dare un senso, di tessere un filo, di produrre una trama anche là dove tutto questo è, volutamente o meno, negato. La fatica o l'impossibilità di costruir(si) una storia provoca il disorientamento, la confusione e persino l'irritazione di fronte a film che, magari apertamente e "sfrontatamente", non ci forniscono gli indizi e non ci permettono di "ancorare" ciò che vediamo e sentiamo al bagaglio personale delle nostre conoscenze ed esperienze. Poichè l'essere umano è, per sua natura, portato a chiedersi il motivo di ciò che accade, e a maggior ragione di ciò che le/gli accade personalmente, la ricerca di senso in tutte le narrazioni (e quella cinematografica non fa eccezione, anzi ne rappresenta una modalità cruciale nell'odierno panorama multimediale) è volta a individuare una catena di eventi, che implichino qualche sorta di relazione causa/effetto, che abbiano luogo in un tempo e in uno spazio, e che coinvolgano (ma non necessariamente) dei personaggi. Come spettatori, diamo per scontato che ciò che vedremo in un film non sarà esattamente la fruizione di un "pezzo" di esperienza così come la viviamo nella vita reale quotidiana. Sappiamo che il film ci presenterà una serie di eventi in modo esplicito, facendoceli vivere attraverso i nostri canali percettivi visivi e uditivi; ma sappiamo anche che molte cose non ci verranno presentate, e che dovremo riempire i "buchi" con la nostra capacità di dedurre e inferire il "non mostrato" con il "mostrato" (è la "strategia di Sherlock Holmes" di cui si parla nel Dossier prima citato). La somma totale degli elementi espliciti, che compaiono sullo schermo, e degli elementi impliciti, cioè di quelli che presumiamo esistano nel mondo rappresentato anche se non ci vengono mostrati, costituisce quella che chiameremo storia, o, in termini più specialistici, la diegesi del film. Questo è ciò che il narratore conosce, ma che non coincide con ciò che lo spettatore sperimenta, per due fondamentali motivi. In primo luogo, nel film, oltre agli elementi diegetici, compaiono elementi non-diegetici, che non appartengono al mondo rappresentato: in primo luogo la colonna sonora, che non è diegetica proprio perchè i personaggi non la possono sentire (si veda la Scheda Suono, in preparazione), ma anche le voci, i rumori ed anche immagini che non hanno la loro origine negli eventi narrati. In secondo luogo, ciò che vediamo e sentiamo come spettatori non è la storia, ma il modo in cui questa è stata (ri)organizzata dal narratore, ossia il racconto, o ciò che chiameremo la trama o l'intreccio (plot). Lo spettatore (ri)crea così nella sua mente la storia, deducendo ciò che non è esplicitamente mostrato e rielaborandone il senso e tenendo ben separati quelli che riconosce come elementi non-diegetici: cf. la Figura 1, ispirata a Barsam e Monahan (Barsam R. e Monahan D. 2011, Looking at movies, Norton). |

Contents 5. Duration and frequency of events 9. Point of view: who knows what, and when?

1. Storytelling and audience Watching a movie is one of the several possibilities we have of enjoying stories. From a friend's account of her summer holidays to a sports commentary, from the simplest joke to the most complex historical novel, we are constantly and fully immersed in a world of stories - stories we tell, stories we are told. Storytelling has now become, in addition to a teaching technique and a way to explore reality, an existential condition, now turned into a rich, constant and nearly obsessive multimedia experience. Films always tell stories - or, at least, spectators expect to see and hear a story, and approach film consumption with a set of "mental tools" which allows (and perhaps forces) them to (re)build what they see and hear in their minds (se the Dossier Expectations, attitudes and strategies). Even the most "expermental" film, even a film which openly sets out not to tell a story, is still subject to the spectator's effort to give meaning, to weave a thread, to produce a plot, even where all this is, more or less willingly, denied. The hard effort implied in (or the impossibility of) building a story causes our bewilderment, confusion and even annoyance when we watch a film which, maybe even openly, does not provide us with the clues and does not allow us to "hook" what we see and hear to our personal store of knowledge and experiences. Since human beings are, by their very nature, prone to asking themselves why something happens (and even more so with respect to what happens to them personally), searching for meaning in all kinds of narration (and film narration is no exception, indeed represents a crucial experience in today's multimedia world) implies identifying a chain of events, which involve some sort of cause/effect relationship, which happen in a certain place at a certain time, and which call (even if not necessarily) for the presence of characters.

2. Story and plot As spectators, we take for granted that what we see in a film isn't the exact equivalent of an event as we experience it in real daily life. We know that the film will show a series of events in an explicit way, asking us to experience them through our sensory (visual and auditory) channels; but we also know that something willl not be shown, and that we will have to "fill in" the gaps through our ability to deduce and infer what is not shown from what is actually shown (this is what we called "the Sherlock Holmes strategy" in the above mentioned Dossier). The sum total of the explicit elements, which appear on the screen, and of the implicit elements, i.e. those which we assume to exist in the film's world even though they are not shown, represents what we call the story, or, using a more specialised term, the film's diegesis: this is what the narrator knows, although it may not be what we experience, for two crucial reasons. Firstly, a film consists of both diegetic and non-diegetic elements: the latter do not belong to the film's world - first and foremost the film's musical score, which is not diegetic for the very fact that characters cannot hear it (see the Outline Sound, in preparation), but also the voices, noises and even images which do not originate from the story events. Secondly, what we see and hear as spectators is not the story, but the way in which this has been (re)organised by the narrator, i.e. what we call the plot. Spectators (re)create in their minds the story, by deducing what is not explicitly shown and re-processing its meaning - and by keeping separate what they recognize as non-diegetic elements: see Figure 1, inspired by Barsam and Monahan (Barsam R. & Monahan D. 2011, Looking at movies, Norton).

|

(1) Storia vs trama/Story vs plot |

|

|

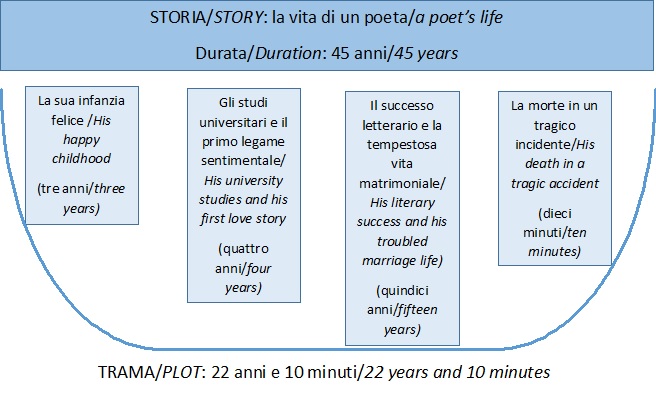

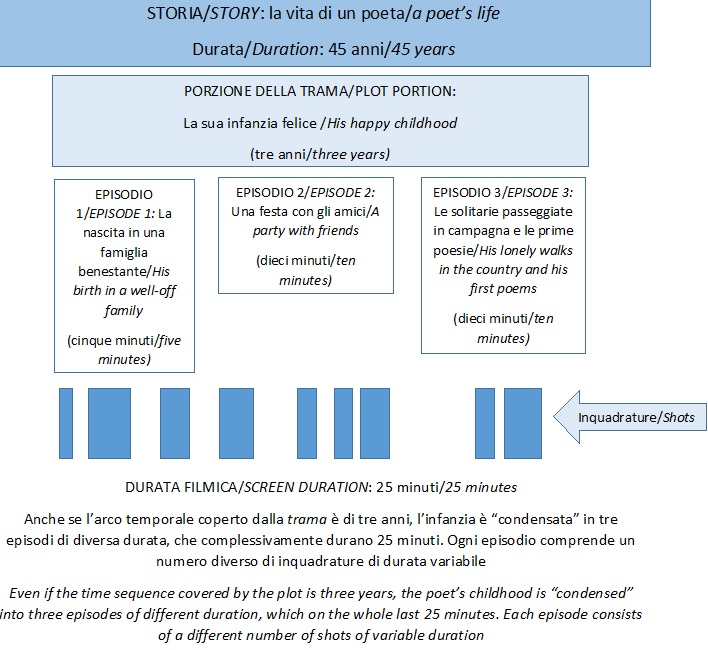

3. La dimensione temporale Siamo ben consapevoli che la durata di un film non coincide (salvo eccezioni) con la durata della storia, e che anche la trama ci mostra "spezzoni" selezionati dell'intera storia. Un film biografico, ad esempio, comprende la storia di tutta una vita, ma la trama seleziona momenti particolari di questa vita. Il film, poi, a sua volta condensa questi momenti comprimendone la durata effettiva. Il film Gandhi (di Richard Attenborough, GB 1982), ad esempio, racconta la storia della vita del Mahatma, ma la trama seleziona episodi significativi di questa vita, come la sua espulsione da un vagone di prima classe in quanto giovane indiano in Sud Africa, i momenti cruciali della proclamazione dell'indipendenza dell'India, fino all'episodio del suo assassinio. Ma il film condensa a sua volta questi episodi comprimendone la durata: di ogni episodio ci vengono mostrati solo momenti significativi, in modo tale che nel complesso la durata del film è di 187 minuti. Le Figure 2 e 3, ispirate ancora da Barsam e Monahan, mostrano in forma grafica queste relazioni temporali. |

3. The time dimension We are well aware that a film's duration does not coincide (with due exceptions) with the duration of the story, and that even the plot shows us selected "pieces" of the whole story. A biopic (a biographical film), for instance, tells the story of a whole life, but the plot selects particular moments in this life. The film then concentrates on these moments by compressing their actual duration. The film Gandhi (by Richard Attenborough, GB 1982), for example, tells the story of the Mahatma's life, but its plot selects meaningful moments in his life, such as being turned out from a first class coach as a young Indian in South Africa, the crucial times of the declaration of India's independence, until his assassination. But the film then condenses these events by compressing their duration: we are shown only meaningful moments of each event, so that on the whole the film's duration is 187 minutes. Figures 2 and 3, inspired by Barsam and Monahan, show graphically these temporal relationships. |

(2) La durata della storia e la durata della trama/Story duration and plot duration |

|

(3) La durata della trama e la durata filmica/Plot duration and screen duration |

|

|

4. L'ordine

cronologico Mentre il tempo della storia rispetta l'ordine cronologico in cui si susseguono gli eventi narrati, ciò non necessariamente accade per il tempo della trama, che, anzi, spesso se ne discosta in modo significativo, contribuendo in modo importante al ritmo totale di un film. Ad esempio, la storia tipica di un film "giallo" o "thriller" comprende la concezione di un delitto, la sua organizzazione, la sua realizzazione, la scoperta del cadavere, le indagini della polizia, la scoperta del colpevole e di come questi abbia concepito, pianificato e realizzato l'intero crimine. Ma non è detto che la trama del film segua per forza di cose questa sequenza: sono possibili moltissime varianti, che hanno tutte come conseguenza di modificare l'ordine cronologico "naturale". I film di Hitchcock sono esemplari, tra l'altro, proprio per la varietà dei modi di strutturare i tempi dell'intreccio. In Il delitto perfetto (USA 1954), la trama segue più o meno il modello "lineare" che abbiamo appena descritto: il marito concepisce e pianifica l'assassinio della moglie, e un delitto viene commesso - anche se la vittima è il sicario - cui segue la concezione di un piano alternativo da parte del marito. Nel contempo, la polizia inizia e conduce le indagini, che porteranno prima all'incriminazione della moglie e poi alla scoperta del vero responsabile di tutto. L'ordine degli eventi è dunque strettamente cronologico. Al contrario, in Paura in palcoscenico (USA 1950), un flashback poco dopo l'inizio del film ci racconta l'antefatto e ci indica subito l'assassino, salvo poi, nel corso delle indagini e di alterne vicende, scoprire che il flashback era falso (un raro caso di manipolazione scoperta del pubblico da parte di Hitchcock!). Altri film, come La fiamma del peccato (USA 1944) e Viale del tramonto (USA 1950, entrambi di Billy Wilder, e Eva contro Eva (di Joseph L. Mankiewicz, USA 1950), consistono quasi esclusivamente di un lungo flashback, con una breve introduzione e una breve conclusione situate nel "presente" (nel secondo film, il flashback viene addirittura introdotto dal protagonista morto, il cui corpo galleggia in una piscina - vedi il video qui sotto a sinistra). |

4. Chronological order While story time follows the chronological order of the events, this does not necessarily happen for plot time, which is often quite different, thus defining the film's total rhythm. For example, the typical story of a thriller or "detective" film includes the planning of a crime, its organization, its realization, the discovery of the victim, the police investigation, the discovery of the guilty party and of how s/he has devised, planned and realised the whole operation. However, the film plot may not necessarily follow this sequence: many variations are possible and each of them implies a change in the "natural" chronological order. Hitchcock's films are prominent, among other things, for the variety of the ways in which plot time is structured. In Dial M for Murder (USA 1954), the plot more or less follows the "linear" path which we have just described: the husband plans his wife's murder, and a crime is committed - although the victim is the hired assassin - which is followed by the husband devising an alternative plan. In the meantime, police investigate and this soon leads to the wife being charged of the murder and eventually to the discovery of the real criminal. The order of the events is thus strictly chronological. On the other hand, in Stage fright (USA 1950), a flashback at the beginning of the film tells us about a crime and shows us the identity of the murderer - but then, following police investigations and other secondary events, we discover that the flashback was actually false (a rare case of Hitchcock's overt manipulation of the audience's expectations!). Other films, like Double indemnity (USA 1944) and Sunset Boulevard (USA 1950), both by Billy Wilder, and All about Eve (by Joseph L. Mankievicz, USA 1950), consist almost exclusively of a long flashback, with a short introduction and a short conclusion situated in the "present" of the story (in the second film, the flashback is even narrated by the dead protagonist, whose corpse we see floating in a swimming-pool - you can watch this scene below right). |

|

Italiano English Viale del tramonto/Sunset Boulevard (di/by Billy Wilder, USA 1950) |

|

| Un caso

ancora più particolare è rappresentato da

Tradimenti (di David

Jones, GB 1983 - il film completo, in inglese con sottotioli, è visibile

qui), che

narra la storia di una coppia di amanti, cominciando da un loro incontro

dopo la fine della loro relazione, e risalendo man mano all'indietro nel

tempo, alla crisi del loro rapporto, ai momenti felici trascorsi

assieme, fino ad arrivare, nell'ultima sequenza, all'occasione che li

aveva fatti conoscere per la prima volta. In definitiva, l'ordine cronologico può essere sottoposto a diversi processi di alternanza tra passato (flashback) e presente, o, più raramente, tra presente e futuro (flashforward), processi che sono stati anche definiti con il termine di anacronia (da non confondere con il termine acronia, che indica invece una mancanza di ordine o una confusione dei tempi). 5. La durata e la frequenza degli eventi Così come è possibile variare l'ordine cronologico degli eventi, è altrettanto possibile agire sulla loro durata e sulla loro frequenza: la durata di un episodio della storia può essere espansa oppure compressa nella durata della rispettiva trama, e lo stesso episodio può essere riproposto più di una volta nella trama. In altre parole, si possono concepire alternative alla linearità dell'equazione "durata della storia = durata del racconto" (narrazione dunque in tempo reale, come accade in un normale dialogo) e alla regola di mostrare un evento una sola volta, optando invece per la sua reiterazione. Sono così possibili pause, formate da momenti che servono come descrizione, commento o digressione rispetto alla narrazione vera e propria: l'immagine può risultare "vuota", nel senso che mancano elementi diegetici, ossia che si possono ricondurre al mondo rappresentato - fino al fermo immagine o fermo fotogramma, in cui l'inquadratura viene "congelata" (frozen frame), spesso con il protagonista che "guarda in macchina", cioè verso il pubblico. Forse il più famoso di questi fermo immagine si trova alla fine di I quattrocento colpi (vedi il video qui sotto), in cui il protagonista è un ragazzino che, dopo molte vicende, scappa dal riformatorio e corre verso il mare, che non ha mai visto. Appena messi i piedi nell'acqua, volge lo sguardo verso di noi: uno sguardo fisso, che non solo lascia il finale aperto, ma ci sembra comunicare l'indefinitezza della sua situazione e l'incertezza di come proseguirà la sua vita. |

An even

more peculiar case is Betrayal

(by

David Jones, GB 1983 - the full film is available

here), which tells the story of two lovers, starting

from their meeting after the end of their relationship, and gradually

tracing back to the crisis of their relationship and the happy

times spent together, and ending, in the final sequence, with a party

which marked their first meeting. Thus chronological order can be subject to different variations, alternating between the past (flashback) and the present, or, although less frequently, between the present and the future (flashforward): this treatment of time has been called anachrony (not to be confused with achrony, which refers to the lack of chronological order or a confusion of time sequences). 5. Duration and frequency of events Just as it it possible to change the chronological order of events, it is possible to vary their duration and frequency: the duration of a single episode of the story can be expanded or compressed in the duration of the corresponding plot, and the same episode can be shown more than once in the plot. In other words, there can be alternatives to the linear equation "story duration = plot duration" (which means real time narration, as in a normal dialogue) and to the rule of showing an event just once - choosing to show it several times. Thus there can be pauses, or moments which serve as description, comment or digression with respect to the real narration: the image can look "empty", i.e. lacking in diegetic elements, or elements which clearly belong to the world of the film - the extreme example being the so-called frozen frame, when the character often looks towards the camera, i.e. towards the audience. The most famous frozen frame is perhaps the one shown at the end of The 400 blows (watch the video below) in which the protagonist is a teenager who eventually escapes from a community home and runs towards the sea, which he has never seen. As soon as he steps into the sea, he turns his eyes towards us: a fixed glance, which leaves the ending open to interpretation, as well as communicating the indefinite nature of the situation and the uncertainty which awaits him in the future. |

|

I quattrocento colpi/Les quatre cents coups/The four hundred blows (di/by François Truffaut, F 1959) |

|

|

Altri finali sono rimasti famosi per l'inquadratura che fissa, "raggela"

l'azione. Al termine di Butch Cassidy (vedi il video qui sotto

a sinistra), l'ultima inquadratura ci mostra i due protagonisti (i

banditi Butch Cassidy e Sundance Kid) che, assediati all'interno di una

casa da un plotone di soldati, si lanciano fuori, pistole alla mano,

andando incontro a morte certa - che però noi non vediamo sullo schermo

(vedi il video qui sotto a sinistra).

Allo stesso modo, in Thelma & Louise, l'ultima inquadratura "congela" l'auto lanciata a tutta velocità

nel vuoto di un canyon, risparmiandoci la visione della fine tragica

delle due donne (vedi il video qui sotto a destra). |

Other film endings have become famous for the final frame, which

"freezes" the action. At the end of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance

Kid (watch video below left), the last shot shows the two outlaws

who, besieged by a company of soldiers, launch themselves out of

the house, holding their guns, running towards their death - which we do

not see on the screen (watch the video below left). In the

same way, in Thelma & Louise, the last shot "freezes" the

car speeding out into space above a canyon - saving us from watching the

two women's tragical end (watch the video below right). |

|

Butch Cassidy/Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (di/by George Roy Hill, USA 1969) |

Thelma & Louise (di/by Ridley Scott, USA 1991) |

|

Al contrario, un evento, ad esempio il procedere della banda di Alex in

Arancia meccanica (vedi il video qui sotto a sinistra), può essere spesso filmato a velocità rallentata (slow motion

o ralenti): la durata effettiva viene espansa, aumentando così

la drammaticità dell'azione e il senso di violenza incombente (scena

visibile qui). A questa

relazione di espansione si contrappone la relazione di

contrazione del tempo della storia, quando, come in un sommario, si

fa procedere con un ritmo più spedito l'intreccio, eliminando i "tempi

morti" o comunque insignificanti, o si velocizza il passare del tempo,

come con gli ormai classici espedienti dello sfogliare velocemente i

fogli di un calendario, o del mostrare in rapida successione diversi

giornali (si vedano gli esempi forniti nella Scheda

Altri aspetti della ripresa). |

At the opposite end, an event, like Alex's gang moving along towards

their next crime in A clockwork orange (watch the video below

right), can be filmed in slow motion (ralenti): the actual

duration is expanded, thus increasing the dramatic impact of the action

and the sense of impending violence (you can watch this scene

here). This

way of expanding the duration of a shot contrasts with a way of

condensing story time, when, as in a summary, the plot is carried

forward at a quicker pace, by eliminating actions which are at a

standstill, or by speeding up the passage of time: some devices to

obtain this result have commonly been used for a long time, such as

showing the pages of a diary (or different editions of a newspaper) been

quickly skimmed (see the examples in the Outline

Other aspects of shooting). |

|

Italiano English Arancia meccanica/A clockwork orange (di/by Stanley Kubrick, GB 1971) |

|

|

Si realizzano così

ellissi temporali di varia durata e di funzioni differenti: il

non mostrare un evento nella sua interezza, o l'interrompere un'azione

nel corso del suo svolgimento, può rispondere a scopi ben precisi: ad

esempio, per creare dubbi o suspense nello spettatore o per censurare

un'immagine. Un esempio magistrale della contrazione dei tempi si ha

alla fine di Intrigo internazionale (vedi il video qui sotto), in cui Eva

(Eva Marie Saint)

è appesa alla mano di Roger (Cary Grant) a strapiombo sul Monte Rushmore. Con

un ultimo disperato sforzo, Roger riesce a sollevare la donna,

salvandola così dal precipizio ... ma mentre la solleva uno stacco

improvviso fa coincidere l'azione con Roger che solleva Eva ...

verso la sua cuccetta di un vagone letto, anticipando così il lieto

fine. Subito dopo, il treno entra in galleria e, con la tipica ironia di Hitchcock, allo spettatore viene

lasciato solo immaginare cosa sta per succedere ... |

In this way it is possible to carry out temporal ellipses of varying

duration and functions: not showing an event in its entirety, or

interrupting an action being performed, can achieve well-defined goals:

for instance, creating doubts or suspense in the audience, or censoring

an image. A masterful example of time contraction appears at the end of

North by northwest (watch

the video below),

when Eva (Eva Marie Saint) is hanging from Roger's (Cary Grant) hand on

the edge of a precipice on Mount Rushmore. With a last desperate effort,

Roger manages to heave the woman onto himself, thus saving her from

certain death ... but as he heaves her up, a sudden cut shows Roger

heaving Eva up ... into his bed in a sleeping car, thus

anticipating the happy end. Immediately after this, the train enters a

tunnel and, with Hitchcock's typical irony, the audience is left to

imagine what is going to happen next ... |

|

Intrigo internazionale/North by northwest (di/by Alfred Hitchcock, USA 1959) |

|

|

Altre volte, e specialmente nel cinema (spesso sbrigativamente) definito

"d'avanguardia" o "d'autore", l'ellisse temporale può avere una durata

indefinita, che incide fortemente sulla narrazione rendendola ambigua se

non scarsamente decifrabile. In questi casi, una volta che gli

spettatori hanno avuto modo di "leggere" l'immagine nel suo

portato diegetico (cioè della storia e del mondo rappresentati), è come

se venisse loro concesso (o imposto?) ulteriore tempo per "riflettere"

su quanto stanno vedendo. Questo cinema, che sollecita uno sguardo più

attento e consapevole, svelando, almeno in parte, il meccanismo centrale

della macchina da presa "che si manifesta", si contrappone a quello che

è stato chiamato "cinema della trasparenza" (in primo luogo, il cinema

classico hollywodiano), centrato invece sugli

eventi e sulla loro successione chiara ed esplicita, che occulta i

meccanismi della ripresa proprio per rendere più fluida l'esperienza

della visione. Quanto alla frequenza, è possibile, in alternativa al semplice raccontare una sola volta ciò che è avvenuto proprio una sola volta, mostrare più volte ciò che effettivamente è accaduto più volte, o, al contrario, mostrare più volte ciò che è accaduto una sola volta. E' celebre, nel film Rashomon (di Akira Kurosawa, Giappone 1950) la ripetizione dello stesso evento, che accade nella storia una sola volta ma che nella trama viene reiterato più volte, visto ogni volta da un personaggio diverso e quindi da molteplici punti di vista. Ma il cinema può anche aver bisogno di mostrare una sola volta (o poche volte) ciò che accade magari regolarmente nella vita di un personaggio: ad esempio, in Il ladro (vedi il video qui sotto) il protagonista, che lavora fino a tarda notte come musicista in un night club, ci viene mostrato mentre, alla fine della serata, ripone il suo strumento, prende il metro, legge il giornale, arriva a casa dove trova la moglie e i figli ... Tutto questo ci viene fatto vedere una sola volta, ma, come sottolinea anche la voce "off" di Hitchcock nel trailer, si tratta di una routine quotidiana, cioè di azioni ripetute tutte le sere. Questa capacità visiva di trasmettere l'idea di un'azione che si ripete, o che si ripeteva, ci ricorda, nel linguaggio verbale, l'uso dell'imperfetto: è come se il film ci dicesse: "Ogni sera, finiva di lavorare, si metteva il cappotto, usciva dal locale, ecc." |

At other times, and especially in so-called "avant-garde" or "author"

films, the temporal ellipsis can be of indefinite duration: this has a

strong impact on narration, which may become ambiguous if not hardly

understandable. In such cases, once spectators have "read" the image in

its diegetic content (i.e. with reference to the story and its world),

it is as if they were allowed (or obliged?) to spend some extra time to

"reflect" on what they are being shown. This kind of cinema, which

prompts a more careful and conscious approach to film by "disclosing",

at least partially, the central working of the camera, contrasts with

what has been referred to as "transparent cinema" (first and foremost,

classical Hollywood cinema): the latter

is centred on events and their clear and explicit

succession, which hides the shooting mechanisms in order to make the

viewing experience as straightforward as possible. As for frequency, it is possible, in addition to telling only once what has actually happened just once, to show several times what has happened several times, or, on the other hand, to show several times what in the story has happened just once. In Rashomon (by Akira Kurosawa, Japan 1950), an event, which happened only once in the story, is shown several times, each time told by a different character, thus providing several different points of view. However, cinema may need to show just once what regularly happens in the life of a character: for example, in The wrong man (watch the video below) the protagonist, who works till late as a musician in a night club, is shown while, at the end of his day's work, puts away his instrument, takes the underground, reads a paper, gets home to his wife and kids ... All this is shown only once, but, as Hitchcock's "voice off" tells us in the trailer), it is meant to show the man's routine actitvities, something which happens every night. This visual possibility of rendering the idea of a recurring action is similar, in verbal language, to the use of such expressions as "used to" or "would": it is as if the film said, "Every night, he used to stop working at 1 a.m. He would put away his instrument, put on his coat, take the underground, etc.". |

|

Il ladro/The wrong man (di/by Alfred Hitckcock, USA 1956) |

|

|

In definitiva, ritorniamo a quanto più volte abbiamo avuto occasione di

sottolineare (e più dettagliatamente nel Dossier

Aspettative, atteggiamenti e strategie): la trama fornisce

agli spettatori indizi sufficienti ad attivare il loro

processo deduttivo e a crearsi aspettative, così che essi

sono in grado di ricostruire la sequenza cronologica degli eventi, la

loro durata e la loro frequenza. 6. I meccanismi di causa ed effetto Una storia implica inevitabilmente qualche sorta di sviluppo di eventi da uno stadio iniziale ad uno finale (spesso, ma non sempre, diverso dall'iniziale). I fattori che determinano questo intrinseco carattere dinamico di ogni storia sono sostanzialmente riferibili a dei personaggi, di solito visibili fisicamente. Anche per questo aspetto, tuttavia, esistono eccezioni: nel film Lettera a tre mogli (vedi il film completo, in inglese con sottotitoli, qui sotto), ad esempio, il personaggio che mette in moto l'azione (una donna che scrive a tre amiche, dichiarando che quello stesso giorno sarebbe fuggita con il marito di una di loro, senza svelare quale) non è mai mostrato, ma compare solo come voce "off" sin dall'inizio del film. |

We thus come back to what we have already stressed (and in more detail

in the Dossier

Expectations, attitudes and strategies):

the plot provides spectators with enough clues to activate their

deductive process and create expectations, so that they are enabled

to re-construct the chronological sequence of events, their duration and

their frequency. 6. Causes and effects A story inevitably implies some sort of event development from an initial stage to a final stage (the latter being, although not always, different from the former). The factors which influence this intrinsic dynamic feature of every story can basically be referred to characters, who are usually physically visible. There are exceptions in this case too: in A letter to three wives (watch the full film below). for instance, the character who sets the action in motion (a woman who writes a letter to three friends, telling them that that very day she will elope with the husband of one of them, without telling them which one) is never shown: we only hear her "voice off" from the very beginning of the film. |

|

Lettera a tre mogli/A letter to three wives (di/by Joseph L. Mankiewicz, USA 1949) |

|

|

Naturalmente, la catena di cause ed effetti, o di ragioni e conseguenze,

può essere iniziata anche da eventi del mondo umano in generale (come

un'epidemia, un naufragio, un crollo in borsa), del mondo naturale (come

un terremoto, un'eruzione vulcanica, uno squalo) o del mondo

"soprannaturale" o fantastico (come un'invasione di insetti giganti, il

ritorno di "morti viventi", la minaccia di extraterrestri), ed anche da

una qualsiasi combinazione di tutti questi elementi. Ovviamente, la

causa scatenante avvia di solito la reazione di personaggi (umani o

meno), il cui comportamento e le cui scelte fanno avanzare lo sviluppo

della storia. Non è necessario che le cause e gli effetti siano

presentati direttamente ed esplicitamente dalla trama: a volte è

lasciato alle spettatore, come abbiamo già notato in altre occasioni, il

compito di dedurli tramite gli indizi presentati. Inoltre, la trama può mostrare le cause ma non gli effetti, o viceversa, in modo tale da suscitare curiosità, ambiguità di interpretazione, oltre che suspense o addirittura angoscia. In L'invasione degli ultracorpi (di Don Siegel, USA 1956) diverse persone cominciano a comportarsi in modo strano, senza manifestare reazioni emotive, e solo dopo aver mostrato diversi esempi di questo evento inizia lo svelamento della causa (la progressiva sostituzione degli esseri umani con sosia senza emozioni, da parte di extraterrestri). |

Obviously, the chain of causes and effects, or of reasons and

consequences, can also be sparked off by events of the human world

(such as an epidemic, a shipwreck, a fall on the stock exchange), of

the natural world (such as an earthquake, a volcanic eruption, a shark)

or of the "supernatural" or fantasy world (such as an invasion of giant

insects, the return of the "living dead", some menacing

extraterrestrials), as well as by any combination of all these elements.

The original cause sets in motion the (human) characters' reaction,

whose behaviour and choices allow the story to develop. Causes and/or

effects may not be directly and explicitly shown by the plot: sometimes,

as we said on other occasions, the audience is left with the task of

inferring them through the clues offered by the film. Besides, the plot may show the causes but not the effects, or viceversa, in order to arouse the audience's curiosity, ambiguous interpretation, suspense or even anguish. In Invasion of the body snatchers (by Don Siegel, USA 1956) many people start behaving in a strange way, without showing any emotional response, and only after showing several examples of this event we are told the actual cause (the progressive substitution of human beings with their doubles by extraterrestrials). |

|

Italiano English L'invasione degli ultracorpi/Invasion of the body snatchers (di/by Don Siegel, USA 1956) |

|

|

In Il villaggio dei dannati (di Wolf Rilla, GB

1960), una comunità

di un piccolo paese viene colta da un improvviso, temporaneo attacco di

sonno, e molte donne rimangono incinte. Nove mesi dopo nasce un gruppo

di bambini molto simili tra loro e in possesso di strani poteri. La

causa ci viene svelata solo verso la fine del film, ed è ancora una

volta fatta risalire all'opera di extraterrestri. Al contrario, in

Jurassic Park (di Steven Spierlberg, USA 1993) la causa di ciò che accadrà nella maggior parte

del film ci è subito mostrata: la ri-creazione di dinosauri in

laboratorio, inizialmente presentata come esperimento non pericoloso, ma

che si rivelerà in realtà una gigantesca minaccia per gli esseri umani.

In tutti questi casi, è evidente che si gioca sulle aspettative dello

spettatore e sulle sue precedenti conoscenze ed esperienze, filmiche e

non. 7. Lo sviluppo della storia Nella maggior parte delle storie è rintracciabile una progressione a partire da una situazione iniziale (setup), di cui ci vengono fornite le coordinate essenziali (luogo, tempo, personaggi, ecc.), a sua volta seguita da un elemento di conflitto o perturbazione, che mette in moto lo sviluppo degli eventi. In Eva contro Eva, ad esempio, ci viene presentata la protagonista, un'attrice di teatro di grande successo ma non più giovane, Margo (Bette Davis), nel cui camerino veniamo a conoscenza dei principali altri personaggi e del loro carattere. Tra questi si inserisce l'altra principale protagonista, una ragazza, Eva (Anne Baxter), che ogni sera assiste allo spettacolo per l'adorazione che nutre per Margo e per il suo successo. Narrando una serie di sfortunati eventi che le sono capitati (e che risulteranno poi essere falsi), Eva riesce a farsi assumere come segretaria/assistente di Margo. Questa assunzione di fatto introduce l'elemento di conflitto basilare nella trama. Da questo momento assistiamo ad un progressivo sviluppo "ascendente" dell'azione drammatica, in cui i protagonisti sperimentano cambiamenti significativi nelle loro motivazioni, che sono alla base della trama orientata verso uno scopo. Infatti Eva gradualmente ma rapidamente riesce a diventare insostituibile per Margo, fino al punto di imparare a memoria la parte che Margo recita ogni sera a teatro. Attraverso un ciclo di piccoli eventi, Margo, dapprima contenta di avere un'assistente così perfetta, diventa sempre più gelosa e irascibile, provocando reazioni negative nei suoi amici e nell'uomo che ama (il regista dello spettacolo). Una sera Margo non riesce a tornare da un weekend in montagna in tempo per lo spettacolo e qui si giunge al punto di svolta (climax) dell'azione: Eva sostituisce Margo e ottiene uno strepitoso successo. Ma la svolta è duplice, perchè Margo si rende conto della sua stessa caparbietà, dovuta in gran parte al rifiuto di accettare il passare del tempo e le inevitabili conseguenze per la sua carriera. A questo seguono diversi altri avvenimenti, che vedono ora un progressivo sviluppo "discendente" dell'azione: Margo riacquista la sua serenità, accettando la naturale evoluzione della sua carriera e decidendo nel frattempo anche di sposarsi. Ma, ancora una volta, questo sviluppo è parallelo al dispiegarsi della vera natura di Eva, che si rivela un'arrivista senza scrupoli. Si arriva così all'ultima parte della progressione della storia, lo scioglimento finale, in cui Eva vince addirittura un prestigioso premio come migliore attrice: ma, terminata la cerimonia di premiazione, Eva trova nella sua camera d'albergo una ragazza, una sua ammiratrice fanatica, che si offre di farle da assistente ... e, non vista da Eva, prova uno dei suoi bellissimi abiti davanti allo specchio, sognando di diventare un giorno una diva di successo come lei ... Questa struttura dell'azione drammatica, che qui viene presentata come "prototipica" di ogni storia, è naturalmente soggetta ad un'infinità di adattamenti e trasformazioni, ma ben rappresenta lo sviluppo della narrazione cinematografica "classica". Come ebbe a dire Jean-Luc Godard, "Ogni storia deve avere un'inizio, una parte centrale e una conclusione - "ma non necessariamente in questo ordine". 8. I personaggi Si è detto che, anche nei casi in cui l'azione drammatica prende le mosse da eventi, naturali e non, la gran parte dei film presenta personaggi che, proprio grazie alle loro reazioni a quegli eventi, fanno sviluppare la storia attraverso le fasi che abbiamo appena esaminato. I personaggi sono dunque quasi sempre un elemento imprescindibile della narrazione, e con i le loro personalità, tratti psicologici, atteggiamenti e motivazioni giocano essi stessi, con le loro azioni e reazioni un ruolo causale nel progredire della storia. Naturalmente non tutti i personaggi giocano questo ruolo nella stessa misura, e per questo si parla di personaggi maggiori e minori (la cui importanza viene persino riconosciuta dai premi Oscar assegnati al miglior attore/attrice in un ruolo da protagonista o leading role e al miglior attore/attrice in un ruolo di supporto o supporting role). I personaggi maggiori (protagonisti) sono quelli su cui si impernia la storia, o almeno la parte preponderante della storia, e rappresentano spesso qualcuno che deve affrontare delle prove e a cui spesso si oppone un antagonista. Può trattarsi di personaggi famosi, come nei film biografici, o di persone comuni a cui capitano circostanze magari fuori dal comune. Nel corso del tempo l'evolversi delle culture ha provocato cambiamenti sostanziali nelle figure dei protagonisti/antagonisti, che non rappresentano più necessariamente un "eroe" e il suo nemico, o, ancora più genericamente, la lotta del bene contro il male. Certamente molti classici "eroi" sono al servizio di cause "benemerite" (come James Bond che deve lottare contro fanatici terroristi), al pari dei nuovi "supereroi", spesso chiamati a combattere forze più o meno oscure e malevole; ma il confine tra bene e male, o tra personaggi "positivi" e "negativi", tipici di molti generi cinematografici, dal western al noir, dal thriller alla fantascienza, è diventato molto più ambiguo e sfaccettato. Non è raro, ad esempio, trovare poliziotti tormentati da disagi psicologici e dalle motivazioni non sempre cristalline, e, al contrario, antagonisti che presentano lati positivi o che li rendono comunque meno "cattivi" rispetto ai canoni classici. I protagonisti di Heat-La sfida (vedi il video qui sotto a sinistra), ad esempio, sono un professionista del crimine e un detective (il suo cacciatore, a sua volta professionista della lotta ai criminali); ma entrambi sono sostenuti da una motivazione ferrea per quel che ognuno fa, quasi che si tratti di "una vocazione, quasi un'ossessione" (Morandini). Questa almeno parziale sovrapposizione di ruoli un tempo molto più distinti, anche in modo manicheo, è diventata oggi una caratteristica frequente di storie che si svolgono in un mondo che sembra aver perso i suoi valori originali e tradizionali - un universo complesso, ambiguo e spesso difficile da interpretare. |

In

The village of the damned

(by Wolf Rilla, GB 1960), the

community of a small village suddenly falls into a deep sleep, during

which several women get pregnant. Nine months later, they give birth to

a group of exceptionally similar babies, who in time turn out to possess

strange powers. The cause of all this is shown only towards the end of

the film, and is once again the work of extraterrestrial beings. On the

other hand, in Jurassic Park (by Steven Spielberg, USA 1993)

the cause of what will happen later in the film is shown at the very

beginning: the laboratory re-creation of dinosaurs, which is presented

as a safe experiment at the start, only to find out that this will turn

into a terrible threat for human beings. In all such cases, films are

obviously playing with the spectators' expectations and their previous

experience, whether derived from films or from general knowledge. 7. Story development Most stories develop along a progression from a starting situation (setup), which is shown in its main features (place, time, characters. etc.), followed in its turn by an element of conflict or disturbance, which sets in motion the development of the events. In All about Eve, for instance, the protagonist, Margo (Bette Davis) is shown as a very successful actress, now in her forties, in whose dressing room we come to know the other leading characters and their personality. Among these there is the other leading character, Eva (Anne Baxter), who each night attends the performance, enraptured by Margo and her success. Eva, after describing herself as the victim of a series of unfortunate events (which will later be shown to be false), succeeds in becoming Margo's secretary and assistant. This actually introduces the basic conflict in the plot. From this moment on, there is a progressive, "ascending" development of the dramatic action, during which the characters experience significant changes in their motivations, which form the basis of the goal-oriented plot. Eva gradually but rapidly becomes an "irreplaceable" factor in Margo's life, up to the point of learning by heart Margo's role in the play. Through a series of apparently minor events, Margo, who is at first delighted to have such a perfect secreaty, becomes more and more jealous and irritable and sets off negative reactions from her friends, as well as from the man she loves (the play's director). One evening, Margo fails to turn up form a weekend spent in the mountains in time for the performance, and here comes the turning point (climax) of the action: Eva replaces Margo and is extremely successful on the stage. But this climax is double-sided, since Margo starts realising her own stubbornness, which is largely due to her refusal to accept her aging and the inevitable consequences for her career. This is followed by other events, which now see a progressive descending development of the action: Margo's new peace of mind implies the acceptance of the natural evolution of her career as well as her decision to get married. But, once again, this line of development parallels the disclosure of Eva's true nature - a woman who would stop at nothing to achieve her goals. The last part of the story takes up to the final winding-up, when Eva even manages to win a prestigious prize as best new actress. However, once the prize-giving ceremony is over, Eva goes back to her hotel room, only to find a girl, a big fan of hers, who offers herself to be her assistant ... and, not seen by Eva, puts on one of her beautiful dresses in front of a mirror, dreaming to become herself a star one day ... This structure of the dramatic action, which is here presented as "prototypical" of every story, can obviously be subject to an infinite number of adaptations and transformations, but well represents how "classical" film narration usually develops. As Jean-Luc Godard once said, "Every story must have a beginning, a central part and a conclusion - but not necessarily in that order". 8. Characters We said that, even when the action starts from events (natural or other), most films introduce characters who, thanks to their reactions to those events, move the story forward through the stages we have just described. Characters are thus in most cases a necessary element of film narration, and with their personality, psychological traits, attitudes and motivations, as well as with their actions and reactions, play a causal role in story development. Obviously not all characters play this role in the same way, and we can therefore identify major and minor characters (the importance of both is even recognized by the Academy Awards assigned to the best actor/actress in a leading role and to the best actor/actress in a supporting role). Major characters qualify as the corner stone of the story as protagonists, or at least of the most important part of the story, and often represent someone who must face trials against an antagonist. Characters can be well-known personalities, as in biopics, or common people who face problems, sometimes under uncommon circumstances. In the course of time cultural changes have caused substantial changes in the design of both protagonists and antagonists, who no longer necessarily represent a "hero" and her/his enemy, or, in even more general terms, the fight between good and evil. Many classical "heroes" certainly work for a "good" cause (like James Bond fighting against fanatical terrorists), as do the new "superheroes", who are often engaged to fight against dark and evil forces; but the border between good and evil, or between "positive" and "negative" characters, who are often typical of many film genres, from western to noir, from thriller to science fiction, has become more ambiguous and multi-faceted. It is not uncommon, for ezample, to find "cops" or "detectives" torn by psychological dilemmas and moved by not-so-clear motivations, and, at the opposite end, antagonists who show a positive side in their personality and thus look and sound less "evil" compared with the classical "villains". The protagonists of Heat (watch the video bdelow right), for instance, are a hardened criminal and a similarly hardened detective chasing him: however, they are both backed up by an iron motivation for what each of them does, what could be defined as "a vocation, nearly an obsession" (Morandini). This at least partial overlapping of roles, which were once kept well apart, has become a common feature of stories which take place in a world which seems to have lost its original, traditional values - a complex universe, which it is difficult to define and interpret. |

|

Italiano English Heat - La sfida/Heat (di/by Michael Mann, USA 1995 |

|

|

I personaggi minori o secondari sono spesso più di uno, anche

se spesso è possibile riconoscere quello/a che viene premiato/a

con l'Oscar al miglior attore/attrice non protagonista (best

supporting actor/actress). Il ruolo che svolgono è, appunto, di

sostenere l'azione che ruota attorno al personaggio maggiore, entrando

in sintonia o in contrasto con lui/lei e sviluppando così spesso un

filone "secondario" che fa avanzare comunque il livello principale della

trama. Si parla a volte anche di personaggi marginali, il cui

peso nelle vicende è minimo, e che compaiono dunque in brevi o brevissime

sequenze (fino ad arrivare ai cosiddetti camei di personaggi,

magari attori o registi famosi, che fanno solo una breve apparizione

sullo schermo). E' interessante anche distinguere tra personaggi "a tutto tondo", che posseggono cioè una personalità sviluppata, una psicologia approfondita, caratteristiche umane ben riconoscibili, e personaggi "piatti", ossia senza una dimensione psicologica ben determinata. Mentre i primi sono figure complesse, caratterizzate spesso anche da conflitti interiori, e capaci di decisioni e comportamenti imprevedibili e di uno sviluppo nel corso della storia, i secondi sono figure facilmente riconoscibili, "unidimensionali", e dal comportamente abbastanza prevedibile, che non si evolve durante la narrazione. Occorre porre attenzione a non sovrapporre i personaggi maggiori con quelli "a tutto tondo" e i personaggi minori con quelli "piatti": infatti tutte queste figure sono importanti anche, e innanzitutto, per il contributo che danno allo sviluppo dell'azione drammatica. Così Indiana Jones, pur essendo decisamente il protagonista assoluto dei suoi film, non è una personalità complessa e sfaccettata; gli astronauti in 2001: Odissea nello spazio (di Stanley Kubrick, GB 1968) sono tratteggiati quel tanto che basta per renderli antagonisti del computer Hal 9000 (a tutti gli effetti un protagonista del film); delle due donne che ruotano attorno al protagonista de Il laureato (di Mike Nichols, USA 1967), una, la signora Robinson, è un personaggio che in poche scene riesce a rendersi tangibile e complesso, mentre al confronto la seconda, la figlia della signora Robinson, rimane piuttosto "piatto" e non fortemente caratterizzato - anche se entrambe svolgono ruoli altrettanto importanti nella progressione della storia. La caratterizzazione dei personaggi, cioè il modo in cui essi vengono interpretati dagli attori/attrici, si basa sia sull'effettiva interpretazione, sia sulle convenzioni associate ad un tipo di personaggio: da questo punto di vista, le culture sono molto cambiate nel corso del tempo. Ad esempio, tutti hanno presente i personaggi interpretati da John Wayne nei suoi innumerevoli film western: oltre alla bravura dell'attore, giocava anche la caratterizzazione "emblematica" della figura ... Oggi non ci aspettiamo più personaggi che siano subito riconoscibili nelle loro caratteristiche essenziali; anzi, spesso il cinema ci propone figure complesse, ambigue, tormentate, che in un certo senso spetta allo spettatore capire e definire nel corso della narrazione. Certamente, il film deve anche fornire gli indizi, di cui abbiamo spesso parlato, per permettere allo spettatore di spiegare e capire i personaggi; in mancanza di tali indizi, siamo tentati di dare la colpa al film di non aver prodotto personaggi in qualche modo verosimili, oppure siamo costretti a chiederci se queste inverosimiglianze non siano funzionali al significato che il film intende trasmettere. Così, se alla fine del film ci viene data una dettagliata spiegazione (psicoanalitica) dello strano comportamento dello psichiatra in Io ti salverò (di Alfred Hitchcock, USA 1945 - il film completo in italiano è visibile qui), in Memento (di Christopher Nolan, USA 2000) il confine tra realtà, sogno, immaginazione nella mente del protagonista ci lascia alla fine perplessi e incapaci di (ri)costruire una storia lineare (vedi la scena-monologo finale del protagonista qui). Occorre sottolineare che questi diversi modi di caratterizzare i personaggi testimoniano e vanno di pari passo con altrettanti cambiamenti nelle concezioni di spazio e di tempo che sottostanno alla narrazione: siamo ormai abituati ai salti temporali, alle dislocazioni spaziali, alla perdita dei confini tra soggettivo e oggettivo che caratterizzano tanti film odierni (anche se a volte può rimanerci il dubbio che si possa trattare di manierismi registici o di puri esercizi di stile ...). |

Minor or secondary characters are often more than one, although it is

often possible to recognize the one who is awarded the Academy Award for

best actor/actress in a supporting role. The role these

characters play is to support the action involving the major character,

developing a positive (or negative) relationship with her/him, thus

weaving in a secondary "thread" which carries forward the main level of

the plot. There may also be so-called marginal characters, whose

role is reduced to a minimum, therefore appearing in short or very short

sequences (including cameos, or short appearences by well-known

actors or directors). It is also interesting to differentiate between "round" characters, who possess a well-defined personality, deeper psychological traits, well-recognizable human features, and "flat" characters, lacking a well-developed psychological dimension. While the former are complex figures, often showing the signs of internal conflicts, ready to make unpredictable decisions and facing a development throughout the story, the latter are easily recognizable, "unidimensional" figures, whose behaviour is easily predictable, and not allowed to develop much throughout the story. We should be careful not to identify major characters with "round" characters (as well as minor characters with "flat" ones): all these figures actually play important roles in carrying forward the action. Thus Indiana Jones is undoubtedly the protagonist of his films, but is not a complex, multi-faceted personality; the astronauts in 2001: A space odissey (by Stanley Kubrick, GB 1968) are there mainly as the antagonists of the Hal 9000 computer (which is actually one of the main protagonists of the film); of the two women who develop a relationship with the protagonist of The graduate (by Mike Nichols, USA 1967), one, Mrs Robinson, is a character who turns out to be rather complex when compared with her daughter, who remains rather "flat", lacking a strong characterization - although both play crucial roles in the development of the story. Characterization, i.e. the way characters are interpreted by actors/actresses, is based both on actual interpretation and on the conventions associated to character types: from this point of view, culrtures have changed significantly in the course of time. For example, everybody remembers the characters played by John Wayne in his western films: in addition to his acting skills, his "cinematic figure" embodied an emblem of traditional American values which he carried over from film to film ... Today we do not expect characters to be immediately recognized on the basis of their essential personalities: indeed, films often present complex, ambiguous, tormented figures, and in a way it is left to the audience to understand and define them as the story develops. A film must certainly supply clues, which we often referred to, in order to enable the audience to explain and understand the characters: without such clues, we are tempted to blame the film for failing to provide characters who are in some way "true to reality" - or we are obliged to ask ourselves if this lack of verisimilitude is not a way of communicating the intended meaning of the film. Thus, if at the end of Spellbound (by Alfred Hitchcock, USA 1945 - the full film is available here), we are provided with a detailed (psychoanalytical) explanation of the psychiatrist's strange behaviour, in Memento (by Christopher Nolan, USA 2000), the border between reality and dream or imagination in the protagonist's mind leaves us perplexed and unable to (re)construct a linear story (watch the final scene-monologue here). We need to stress that these different ways of building characters match other similar changes in the conception of space and time that underlie each narrative: we are now used to being confronted with time gaps, space changes, and the loss of a clear line between subjective and objective which make up the world(s) shown by "modern" films (even though we may sometimes be left with a doubt that all this may conceal directors' mannerisms or mere exercises in style ...). |

|

Italiano English Memento (di/by Christopher Nolan, USA 2000) |

|

|

9. Il punto di vista: chi sa che cosa, e quando? Un film "mette in scena" una storia, e ciò che vediamo è, di fatto, ciò che vuole e sceglie di farci vedere la macchina da presa (e naturalmente chi la manovra più o meno direttamente, in primis il regista e il direttore della fotografia, ma anche il montatore - vedi la Scheda Montaggio). In molti casi la storia ci viene semplicemente presentata sullo schermo da parte, appunto, di quella che viene a volte chiamata l'istanza narrante. A volte invece la storia viene raccontata da una voce narrante, che non sappiamo chi sia e non appartiene nè ad alcun personaggio nè alla storia narrata, è cioè una voce non-diegetica (voice-over) - in sostanza è ancora un'istanza narrante, un commentatore che può limitarsi, ad esempio, ad una generica e superficiale descrizione di luoghi o circostanze piuttosto che addentrarsi nella psicologia di un personaggio. Può ancora darsi il caso di un personaggio che racconta, non necessariamente tutto quello che sa, e in modo dunque variabile tra l'oggettivo e il soggettivo. In ogni caso, le informazioni che ci vengono fornite possono variare in quantità, qualità, e momento di presentazione. Si pone così la domanda cruciale di stabilire, per ogni momento della storia, chi sa che cosa. La narrazione può così essere onnisciente (senza restrizioni), nel senso che lo spettatore sa, cioè vede e sente, più di ciò che sanno tutti i personaggi; oppure in qualche misura ristretta, di solito limitata a ciò che vede e sente uno o più dei personaggi. Naturalmente questa distinzione non è assoluta, e durante lo svolgimento della trama si possono alternare momenti di narrazione più o meno onnisciente o ristretta: in altre parole, in ogni momento potremmo chiederci se ne sappiamo di più, di meno o tanto quanto i personaggi. Naturalmente questi diversi gradi di oggettività e di soggettività dipendono dalla profondità con cui gli eventi vengono introiettati e vissuti nella mente e nella psicologia dei personaggi: possiamo così avere inquadrature che corrispondono ad un punto di vista o ad un punto di ascolto soggettivo, che ci fa vedere e/o sentire ciò che un certo personaggio vede e/o sente. A questa soggettività nei confronti si immagini e suoni può alternarsi una soggettiva più mentale, che ci porta all'interno della mente di un personaggio, come quando la voce di un personaggio "parla a se stessa", facendoci così entrare nel vivo dei suoi pensieri ed emozioni. I diversi gradi di soggettività/oggettività obbediscono a funzioni diverse: è chiaro, ad esempio, che entrare nella mente del personaggio facilità l'immedesimazione da parte dello spettatore, ed è un elemento importante nella creazione di aspettative nei confronti del personaggio stesso e della storia. D'altro canto, un film può prendersi ampi margini di discrezionalità rispetto alla quantità, qualità e "temporalità" delle informazioni. Fornire più o meno informazioni allo spettatore, e farle più o meno coincidere con quelle in possesso di uno o più personaggi, sta alla base della curiosità, delle aspettative e della suspense che si vuole provocare. A questo proposito è utile citare la differenza tra suspense e sorpresa: Hitchcock, maestro di entrambe, le ha ben descritte in una famosa intervista (vedi il video qui sotto). Sostanzialmente, il regista spiega che se sotto un tavolo è stata piazzata una bomba, ma lo spettatore non lo sa, l'esplosione procura magari cinque o dieci secondi di sorpresa o shock. Ma se invece lo spettatore ne è consapevole, sa che la bomba scoppierà tra cinque minuti, assiste impotente alla conversazione che nel frattempo sta avendo luogo tra due personaggi seduti a quel tavolo, allora avremo procurato una suspense molto più prolungata: se poi ci vengono mostrati uno o più orologi che scandiscono il tempo, la nostra ansia aumenterà e ci verrà da urlare ai personaggi: "Perchè state parlando di queste sciocchezze, non sapete che cosa vi aspetta! Scappate prima che sia troppo tardi!". |

9. Point of view: who knows what, and when? A film "puts on the stage" a story, and what we see is actually what the camera (and obviously the people who are behind it, first and foremost the director, the director of photography and the editor) wants us to see (see the Outline Editing). In many cases the story is simply told on the screen by the film itself acting as a narrator. At other times, though, the story is told by a narrator's voice, which we can't identify as belonging either to the characters or the story being told - what is called non-diegetic voice (or voice-over). In practice, it is still a narrator or a commentator who may simply provide a generic and superficial description of places and circumstances rather than get deeper into a character's psychological traits. And of course we may find a character telling us the story (although not necessarily all that she/he knows, thus leaving possible gaps between subjective and objective narration). In any case, the information we are provided with can vary in quantity, quality and time of presentation. We are thus forced to ask ourselves, at each moment in the story, who knows what. Narration can thus be omniscient (unrestricted), when the audience knows, i.e. sees and hears, more than all the characters know; or in some way restricted, limited to what one or more characters see and hear. Obviously this distinction is not an absolute one, and during plot development the degree of restriction can vary: in other words, at each moment we could ask ourselves if we know more, less or as much as the characters. These different degrees of objectivity and subjectivity also depend on how deep events are engrained in the characters' mind and personality: we can thus have shots which imply a subjective point of view or point of hearing, through which we can see and/or hear what a character actually sees and/or hears. This subjectivity of images and sounds can alternate with a more mental subjectivity, which takes us inside a character's mind, as when a character's voice seems to "talk to itself", so that we share her/his thoughts and feelings. These different degrees of subjectivity/objectivity play different roles: entering a character's mind obviously means facilitating the audience's identification, and is an important factor in creating expectations towards the character and the story. On the other hand, a film can have ample discretionary powers with respect to the quantity, quality and "time management" of information. By providing the audience with more or less information, and by making it overlap with the information that is available to one or more characters, a film can regulate the audience's curiosity, expectations and suspense. Talking about suspense, it is useful to mention the difference between suspense and surprise: Hitchcock, a master of both, described them vividly in a famous interview, which you can watch below. In a nutsheel, the director explained that if a bomb is put under a table, but the spectators don't know anything about it, the explosion can cause five or ten seconds of surprise. However, if the audience is aware of it, knows that the bomb is going to explode in five minutes' time, hopelessly watches the people sitting at the table having a conversation, then the result will be a prolonged suspense: if, on top of that, we are shown one or more clocks inexorably telling the time, our anxiety will increase and we will be tempted to cry out: "Why are you talking about all this nonsense, don't you know what's going to happen? Run away before it's too late!". |

|

Hitchcock spiega la differenza tra "sorpresa" e "suspense"/Hitchcock explains the difference between "surprise" and "suspense" |

|

|

Per concluere, abbiamo accennato più volte ai cambiamenti che sono

avvenuti, nel corso del tempo, nelle modalità di narrazione,

contrapponendo in modo particolare quella che viene considerata la

narrazione classica hollywodiana rispetto alle varie forme di

narrazione "moderne" (si veda ad esempio il Dossier

I film "puzzle" e la narrazione complessa: una

sfida allo spettatore). |

To conclude, we have often mentioned the changes that have taken place, in the course of time, in narrative modalities, contrasting what is considered as classical Hollywood narration with various forms of "modern" narration (see e.g. the Dossier "Puzzle" films and complex storytelling: a challenge to the audience). |

|

Per saperne di più ... * Dal sito Cinescuola: - La narrazione cinetelevisiva * Dal sito Wikipedia: - La narrazione cinematografica * Dal sito Alfafilm: Il linguaggio cinematografico di Gabriele Cecconi: - La narrazione cinematografica * Dal sito ilcorto.it: - Analisi narrativa del film di Elisabetta Manfucci |

|

Want to know more? * From the Elements of cinema website: - Narrative cinema and Elements of a screenplay * From David Bordwell's website: - Three dimensions of film narrative, from Poetics of Cinema * Introduction to narratology, written and designed by Dino Felluga * From the Filmosophy web site: - Film narrative * From the Film Studies for Free website: - More links to Narratology and narration in film and transmedia storytelling * From The living Handbook of Narratology: - Narration in film |

Torna all'inizio della pagina Back to start of page